Here’s a common online dating scenario: I’ll see a blurry group photo of the back of a bunch of rock climbers’ heads or a playa-party pic showing mask-clad Burners and think, “Which one is he? Is that his sister or his polyamorous companion?” Then I’ll scratch my head and sweft. I understand that people who post these pics think that group photos and activity shots show that they have interests and friends. Everyone has interests and friends. But I like to see a clear shot of a guy’s face — his clothed body — and not much else.

In a recent scientific paper made available last month, How Smart Does Your Profile Image Look? Intelligence Estimation from Social Network Profile Images, researchers at the University of Cambridge’s Psychometrics Centre concluded that “intelligent people have fewer faces in their images.” If you’re really an ass hat, you’ll post a photo with your sisters who look like you but are hotter.

Extracting social value from images is part of a newer frontier in artificial intelligence called “deep learning.” Deep learning uses artificial neural networks modeled after the human brain. The artificial networks are faster and more accurate at processing large amounts of data.

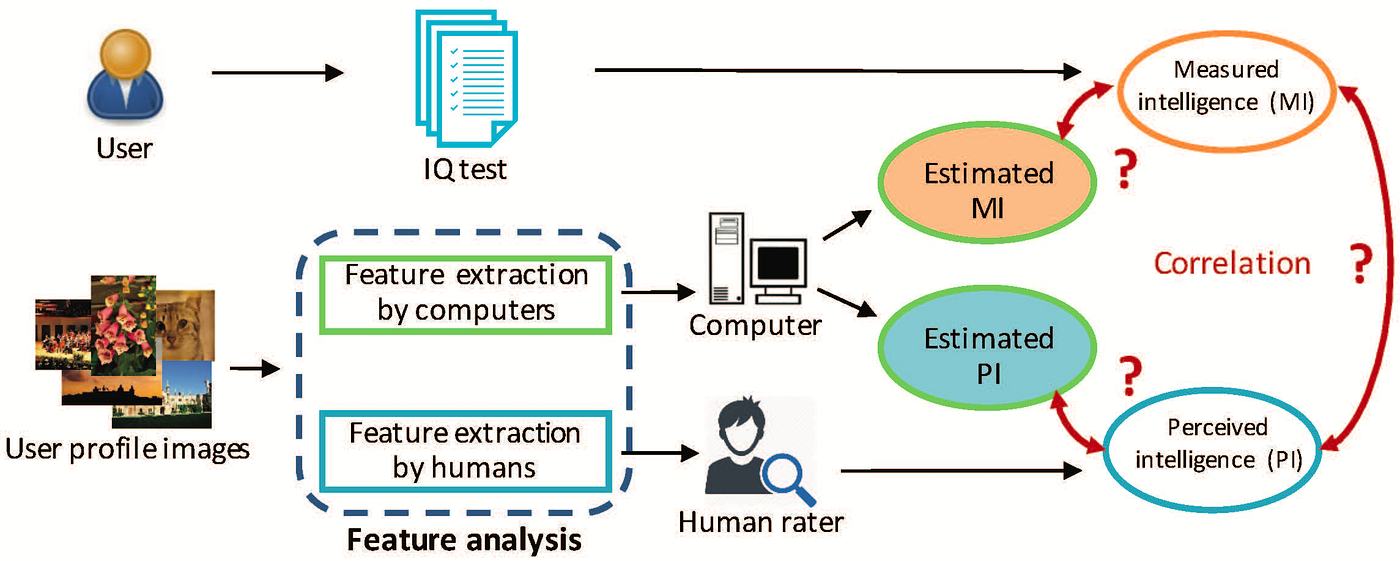

The Cambridge study used the profile images of 1,120 Facebook users. Users were given an IQ test to measure intelligence scores, and their profile photos were shown to other humans in order to estimate their perceived intelligence.

(Disclaimer: the researchers understand that IQ tests are subjective and often involve a socioeconomic, even racist bias. IQ tests do not measure “innate intelligence.” Likewise, the fact that algorithms are mathematical in nature does not mean that they are free from bias; the algorithm used in the study relies on IQ scores and looks at data created by human behavior.)

To develop the algorithm, the researchers trained the computer to conduct feature analysis with a set of images of users with measured (IQ test) and perceived (rated by humans) intelligence scores. The computer used complex mathematical models to find correlations between intelligence scores and image features, such as which visual elements tend to show up in photos of people who score as intelligent. Now the computer can apply this algorithm to new photos it hasn’t yet encountered — in effect, researchers could use these algorithms to predict intelligence on the basis of one’s profile photo. The purpose was to find whether computers can succeed at estimating people’s “real” intelligence and whether computers might help humans avoid inaccurate stereotypes and value judgments on the basis of a profile photo.

The online profile images the researchers used consisted of photos of users’ faces as well as non-face images like cartoons. The images contained behavioral cues such as poses, pets, objects and the presence of other people, which were linked to people’s interests, lifestyles and how they represent themselves on social networks.

According to the researchers, humans use cues to perceive intelligence from images that are not correlated with measured intelligence — such as wearing glasses or having tattoos. A computer will avoid this bias. As the study’s authors wrote, “Most intelligent people in our dataset understand that a profile picture is most effective with a single person, captured in focus and with an uncluttered background.” Less intelligent people present images with the colors pink, purple and red. Humans think that smokers are dumb, according to the study, but if that smoker is wearing green, not showing too much skin and is solo in the photo, the computer will beg to differ.

I asked researcher Dr. Xingjie Wei about the practical implications of the study, and she said, “Surveys and experimental research show that recruiters will search applicants’ social network accounts to get information before making interview decisions, and in most social networks, profile images are public by default. We hope our research can provide insights for people to better manage their self-representations online.”

Wei’s work in intelligence-prediction accuracy indicates that computer algorithms can automatically make intelligence predictions on the basis of profile images better than a human’s random guess. The study should draw our attention to how we manage our photos online, but there is still room to improve the prediction accuracy. Profile pictures won’t be replacing IQ tests anytime soon. Just to be safe, though, why not take down the bathroom selfie of just your naked torso?

I asked Adam Harvey, an artist exploring fashion as camouflage from face-detection technologies and a researcher uncovering knowledge asymmetries in new technologies, about the implications of the Cambridge study. According to Adam, “The general problem with all research in this area is that it’s conflating stereotyping with science. I think it’s important to also consider the historical relationship to the earliest work in this field by Francis Galton, who aimed to infer criminal behavior, disease and, ultimately, someone’s fate purely from a photograph of their face.” (Galton, the father of eugenics, is now condemned for his work, which was considered high-tech in 1883.)

Harvey added, “Unfortunately, there is too much knowledge asymmetry between those who share photos and those who analyze photos. I would argue that this imbalance results in irrational and exuberant data-sharing behavior that is not well aligned with the consequences of data analysis.” In short, people want to share everything online and are not prepared for the repercussions that come with the level of sophisticated analysis that computers bring.

The upside to the Cambridge study and others like it is that the more we know about how our online photos are perceived, the more opportunity we have to change our behaviors when it comes to posting pictures. So take down those group photos. No need for a bikini pic. Gentlemen, please delete that bathroom selfie of your chest. In my case, the photo of me on Bumble wearing a Lumpy Space Princess Halloween costume probably makes me look dumb. She’s a very purple creature.