By Josh Izenberg

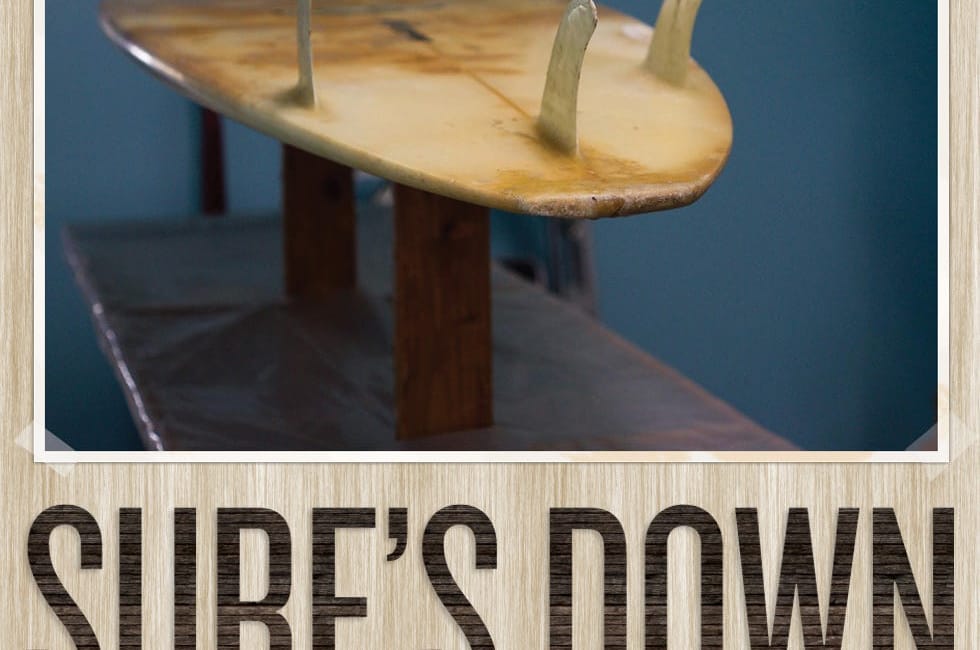

I’d recently started to accumulate a quiver of damaged boards, the way some people collect rare records. My stockpile included a couple six-footers from one garage sale, a gun — a long pointed board, meant for big surf — from another, and an old long board borrowed from a friend. All dented, scraped, and dinged, lying against a fence in my backyard.

So I bought a $12 ding repair kit at Wise Surfboards, watched a few instructional YouTube videos and got to work haphazardly mixing resin and catalyst, slapping on ill-fitting patches, sanding the whole thing by hand, and inhaling fiberglass in the process.

It was a messy and physically harmful experience, but in the end, it got the job done.

My latest acquisition needed more than slapdash bandages, though. Grabbed off Craigslist for $40, it was a 7'10" “fun board” that made Andre the Giant’s face look symmetrical. It seemed okay in the pictures. In fact, it looked fine when I picked it up from a guy named Jim at the Chevron Station on Fell and Masonic.

Upon closer inspection, though, I noticed the damage: dings on the rails, bad repairs on the bottom, and delimitation up front. Also, a

hole in the nose was filled with what appeared to be either insect eggs or mouse droppings.

While the board was best fit for wall decoration, I decided to take it as an opportunity to improve my repair skills. For that, I needed more than YouTube videos. I needed an apprenticeship.

When I called around looking for someone to teach me surfboard repair basics, one name came up every time. All the surf shops in town — Wise, Mollusk Surf Shop, Aqua Surf Shop, even Danny Hess, the local board shaper — said the same thing: “You gotta talk to Alex Martins.”

“Repairing surfboards is easy,” Alex Martins tells me. “Just don’t fuck up the first step. If you fuck up the first step, the rest of the board will be fucked up too.”

His wisdom applies to a lot of things. Cooking. Raising German Shepherds. I’m hoping to pick up more than just Alex’s knowledge of board repair. I’d like to acquire his patience, fluidity, and attention to detail.

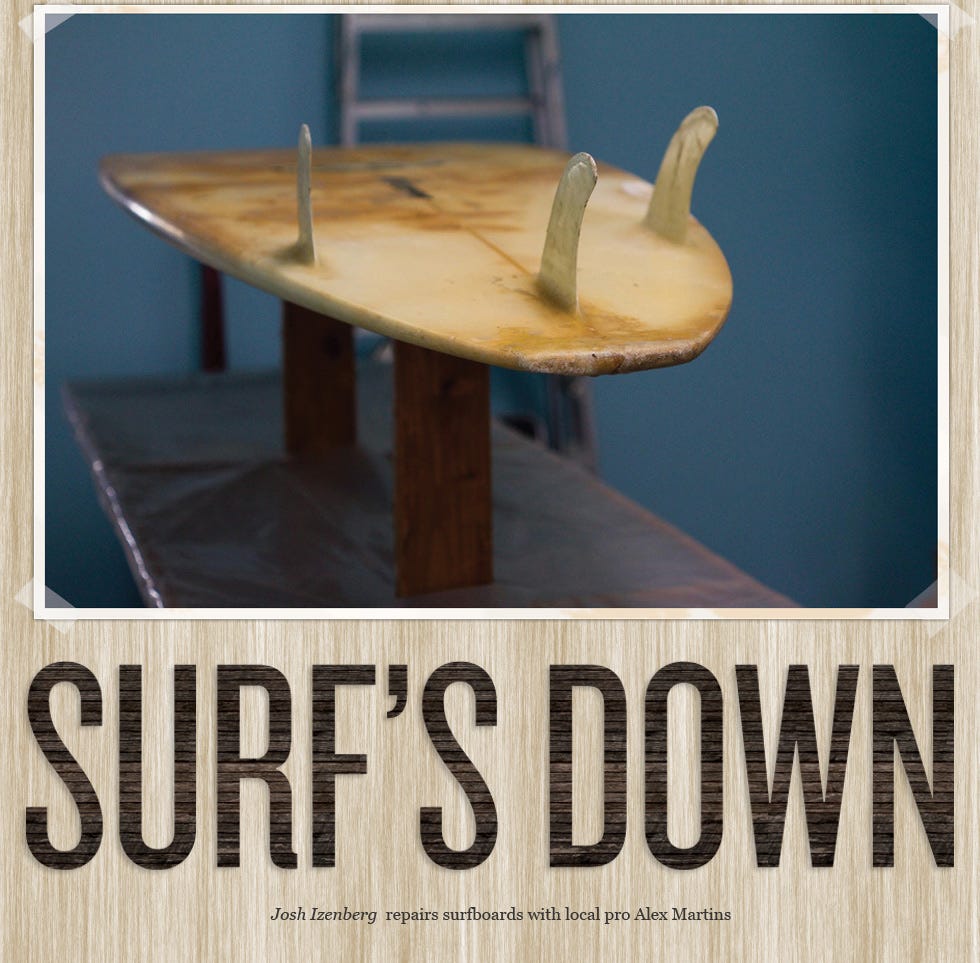

We’re in the back of his board repair shop, which is aptly called Alex Martins’ Surfboard Repair. When you’re the only full-time ding fixer in town, you don’t need a fancy name.

Born in Brazil, Alex moved to California in 1993 in search of better waves. Initially, board repair was something he did for friends, making a little extra money to supplement working in restaurants. He slowly built his reputation and eventually was able to open a shop in South San Francisco to repair boards full time. He moved his operation to a small store in the Outer Sunset in September, on Lawton and 43rd. It’s so new that when I rolled up on the place, he and his wife Sarah were out front eyeing a spot to hang their sign. The paint was still fresh on the walls.

Despite the recent move, there are already a slew of big guns hanging high on the walls in various stages of repair. These are Mavericks boards, designed to surf one of the biggest, most dangerous breaks in the world, half a mile out from Half Moon Bay.

Alex has been surfing Mavericks since 2003 as an alternate in the lineup of top surfers selected by committee to compete in the waves. In February 2010, he made it to the semi-finals after pro-surfer Brock Little’s injury left an open spot in the competition.

A practitioner of Ashtanga yoga, Alex has a calm, deliberate demeanor. I imagine this helps with both meticulous repair and surfing 50-foot skull-crushing waves. Alex likes to do things right.

The backroom of Alex’s shop is mostly empty, save for a huge cylindrical machine sporting a long black hose, whose sole purpose is to suck floating fiberglass particles from the air. Dressed in coveralls with a respirator hanging around his neck, Alex assesses my board, which is laid out horizontally on a stand. “Yeah,” he observes. “This is pretty bad.”

Regardless of whether we can rehabilitate the thing, it’ll be a good practice board for my repair lesson, the fiberglass equivalent of a med school cadaver. We find a good, solid dent on the rear rail to work on. The test case for my lesson.

The first step, Alex tells me, is to cut around the dent with an X-ACTO knife, removing all the splintered fiberglass. Like cleaning a lacerated wound, the goal is to get the hanging shit out of the way. Alex then sands around the ding with his power sander so the forthcoming fiberglass patch we’ll be putting on will have a rough surface to stick to.

The noise of the sander, coupled with Alex’s muffling respirator and thick accent, is making communication difficult. I take in what he’s saying mostly through hand motions. The key, he explains, is to sand in a wide diameter around the ding.

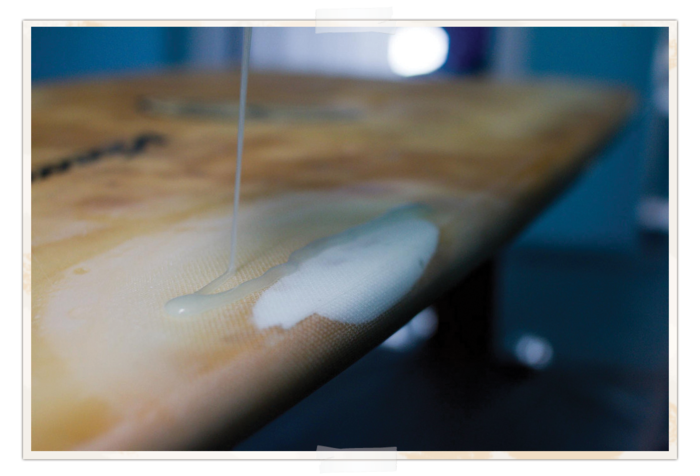

We take the sanded board back to the front room where Alex mixes epoxy resin and hardener together with a wooden spatula. Very important to get the ratio right, he tells me. This is part of “not fucking up the first step.” Two parts resin to one part hardener.

After mixing for a minute or so, Alex adds a little Q-Cel — a white powder that, when folded into the resin mix, turns the whole concoction into a sort of light-blue toothpaste-looking substance. He doesn’t take specific measurements of the Q-Cel. Like a pastry chef

folding in flour, he just knows when everything’s at the proper consistency.

He carefully smoothes the filler into the ding with a small squeegee, following the contours of the board. Use too little filler, he explains, and the patch won’t lay right. Too much and you’ll have to sand the excess down later — and dried filler is a lot harder to sand than fiberglass.

And with that, the ding is filled. Now it just has to dry.

I show up the next week. The Q-Cel has hardened and Alex sands the filler down so it’s perfectly flush with the rest of the board. He then cuts two patches from a roll of mesh fiberglass and lays them over the ding, sealing them to the board with another layer of resin.

By the next evening, the patches have dried. Alex sands it all down again and makes up a batch of hot coat by adding an additional agent to the resin/hardener mix. Using his brush, he covers the fibrous patch with the smooth, viscous liquid, filling in the divots in the fiberglass.

The hot coat has hardened by my fourth and last trip to the shop, and the only thing left to do is sand. From my brief experience, surfboard repair seems to consist mostly of sanding and waiting for things to dry.

Alex works his way from rough to fine grit sandpaper, rubbing a dab of surfboard sealer into the board for a finishing touch. The repair is flawless. The rest of the board still looks like shit, but it’s up to me now to fix the rest.

“You know,” Alex says, taking it all in, “your board’s okay.” He nods approvingly, signaling that somewhere beneath the remaining damage there’s potential. What was once a proud board — Santa Cruz Vernor — may one day surf again. It just needs a little more work.

Technically speaking, I should’ve fixed the hole in the nose. I told Alex I would before taking the board surfing. It’s definitely not watertight. Still, I have to get this thing in the water and Saturday is perfect. The temperature’s in the high 70s and there are nice waves in Pacifica. Out on the beach, I wonder if other surfers notice the board, which looks like a mummy whose wrapping is falling off.

I paddle out. The board is smaller than I’m used to, but feels solid and buoyant. It’s a good transition from the heavy long board I’m used to.

I miss the first couple sets, and then a nice, clean swell arrives. I paddle for it, feeling the momentum take hold. I cruise down the wave face, picking up speed. The board is fast.

I push off the rails and pop up — and for a fraction of a second, I’m cruising. But I’ve forgotten to wax the board and when I shift my weight, my legs fly out from under me and I eat saltwater.

I learned how to fix the ding. Now, I just need to learn how to fix the surfer.

Interested in surfing on the cheap?

San Francisco abounds with inexpensive, used boards. Check the Craigslist sporting goods section, or just cruise some local garage sales. If you’re new to surfing, be sure to start with a long board.

Don’t worry about a few dings. You can call Alex Martins at (415) 699–2380. He charges $45 for the first repair and $15 for each additional ding.

Or buy a $12 ding repair kit at Wise Surfboards and do it yourself. If you’re really serious about board repair, you might also want to invest in a power sander. And if you’re serious about living to a ripe old age, consider getting a respirator while you’re at it.

Design: Jess Taich