In February, I returned to San Francisco from Hong Kong after a month in my hometown. My trip had coincided with canceled Chinese New Year gatherings and near-universal mask-wearing across the city. Hong Kong’s societal-level hypervigilance conjured up many childhood memories of SARS. My family urged me to maintain my rigorous regimens once back in the U.S.— from disinfecting clothes immediately after returning home to pressing elevator buttons with toothpicks.

Heeding their advice, I bought hand sanitizer, soap, and Lysol wipes for my apartment in San Francisco, which I share with three roommates. With news that the coronavirus was already quietly circulating within the community, I made lifestyle changes — washing my hands often and canceling all my non-essential plans that involved face-to-face contact.

The problem was, despite my efforts to stay germ-free, the people I share a home with didn’t have the same sense of concern. A few days after my return to the U.S., my roommate developed a dry, hacking cough. “It’s probably just a cold,” he reassured me and my other housemates, adding that he thought the coronavirus was overhyped. “This is no different than the flu. I don’t see the point in altering my behavior.”

All of my roommates continued taking Muni, attending events around town, and telling me how my fears are unwarranted. My frustration and helplessness mounted as I monitored the rising number of cases in the Bay Area and witnessed my roommates’ apathetic decisions and questionable hygiene.

It’s hard to tell your roommate “I know you haven’t been washing your hands” without sounding aggressive.

I realize that I sometimes sound alarmist to my American-born roommates, maybe even hysterical. But I’m not hoarding toilet paper, hand sanitizer, or canned goods. I’ve controlled the itch to scour Walgreens for face masks. Instead, I’m simply advocating for our household to take preventative measures, such as greater hygiene awareness and social distancing. The personal responsibility practices I’ve imported from Hong Kong have kept my hometown relatively healthy in the current outbreak; call them hard-learned lessons from SARS.

But it’s hard to tell your roommate “I know you haven’t been washing your hands” without sounding aggressive. After timidly barricading myself in my bedroom for four days, until my roommate recovered from his mysterious cough, I realized this self-imposed isolation was not only mentally and physically unsustainable, but also futile given the lackadaisical attitudes of my house.

What I’m facing — my health at the behest of the people I share a home with — is something thousands are also grappling with, especially in the Bay Area, where living with roommates is essential for more than 60% of the rental population due to the most expensive housing costs in the country. As the coronavirus continues to spread and anxiety heightens, roommates around the city — and the country, and the world — should be having conversations about the risks of co-living as a potential pandemic looms.

I decided to see if I was the only one feeling anxious about potential coronavirus exposure due to their roommates’ habits. Sean Keenan, an engineer who lives with five roommates in a Millbrae single-family home, told me it’s a conversation his house has had, but that they’re remaining calm.

“My roommates and I have been discussing the importance of frequent handwashing,” Keenan said. “But we decided we’re not going to stock up for food/supplies.”

In San Francisco, tighter spaces of communal living — sleeping pods and dorm-like apartments — have become more common as housing costs rise. I was compelled to reach out to those managing high-density co-living spaces to find out if their greater responsibilities resulted in greater concern.

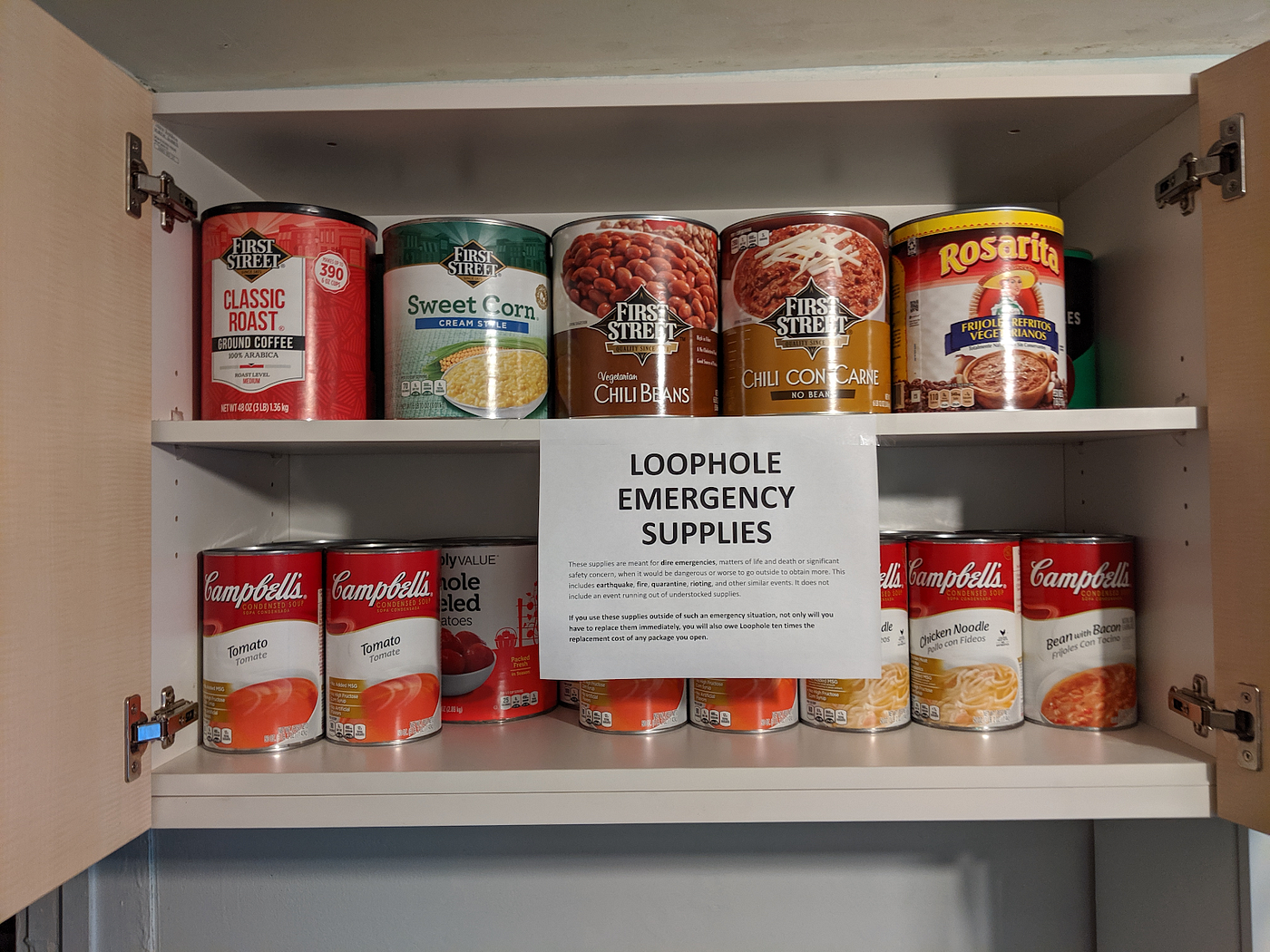

“I’m pretty certain there will be an outbreak that eventually infects most of the people in the city,” said Clarence “Sparr” Risher, the co-founder of Loophole, a 4,200-square-foot co-living arts and events space in SOMA with 11 residents. “Our efforts are meant to slow down the spread, so that the peak health care need is lower over the course of a longer outbreak.”

Residents recently started a discussion about the virus on Slack, including debating whether to cancel all upcoming community events such as comedy nights and yoga classes. They’re continuing the discussion in an in-person meeting this week. Additionally, they’ve been using the current prepping frenzy as motivation for other emergency (mostly earthquake) preparedness by stocking up on food and supplies.

It appears that both PodShare and Starcity are taking preventative measures, but don’t have concrete plans in place if an outbreak were to occur under their roofs.

Jon Dishotsky, the CEO and co-founder of Starcity — a California-based startup that runs “dorm-style” co-living arrangements where residents share kitchens and other living spaces — said the company is taking the coronavirus seriously. Management is providing more frequent disinfecting and extra paper towels, hand sanitizer, and Clorox wipes in shared spaces and high traffic areas of the homes. They have told residents to use a personal towel (or a paper towel) to dry hands instead of the communal towels if they feel sick.

PodShare, a SoCal-based startup with a location in the Tenderloin, is taking similar measures. PodShare operates a hostel-like “subscription housing” model; think open bunk beds, communal spaces, and lockers for your stuff for $1,200 a month. I spoke to Elvina Beck, the CEO of PodShare, and Rebecca Nashleanas, her COO, who said they’re trying to do their best for residents in the absence of official guidance from the CDC on co-living, relying instead on information provided by the media. To prepare for the potential need for extra hand sanitizers beyond their current store-bought stock, they are also making homemade ones with aloe vera gel and alcohol.

It appears that both PodShare and Starcity are taking preventative measures, but don’t have concrete plans in place if an outbreak were to occur under their roofs. When I asked both CEOs what steps they’d take if a resident were to be diagnosed with COVID-19, they didn’t provide concrete measures but said they would consult experts on appropriate steps should that happen. Dishotsky emphasized that Starcity has a robust emergency response protocol for community health events such as seizures, asthma, and heat stroke, but given the uncertainty and newness of the coronavirus, they are updating their protocols per the CDC’s guidelines regularly.

Given the nature of these living situations, though, it could be difficult to quarantine or deal with an outbreak. Paul Hanson Clark, who stayed in PodShare’s Los Feliz location in early January, told me he cut his one-week trip short after an unpleasant encounter with a sickly pod neighbor who coughed loudly throughout the night. He complained and requested a partial refund from PodShare, which he said the company refused, though they did offer to transfer him to a different location. He declined.

“I’m not an expert, but based on my experience PodShare is absolutely willing to house sick guests,” Clark wrote, “There weren’t easily accessible disinfectant wipes, hand sanitizer, or anything along those lines. In my experience, PodShare wasn’t capable of taking basic health precautions in a normal circumstance, and while I don’t want to speculate, that doesn’t bode well for how they would handle a public health crisis.”

When I asked PodShare’s Elvina Beck about Clark’s comments, and whether guests can expect new policies if concerned about sick pod neighbors, she noted that the guest’s January stay was before the coronavirus became a concern and a state of emergency was issued. “Of course everyone’s protective measures have changed in the course of two months,” she wrote in a statement. “Furthermore, this guest was offered another accommodation a few miles away, since we offer unlimited transfers, but declined for personal reasons.”

When I had spoken to Beck in our initial conversation, I sensed frustration about the lack of clear and concise information from official government channels. “It’s all really new and fast,” Beck said. “We want everyone to have more access to local clinics and receive free testing. How else are we going to find out if guests have the common flu and not something else?”

Every apartment is a microcosm of the entire country.

Back in my apartment, as awkward as it was, I decided to sit down my roommates to express my discomfort at our varied levels of precaution. With increasingly dire warnings, my roommates agreed they might’ve been a bit too cavalier. Although they have yet to fully implement my stringent recommendations, I’ve found relief in the uptick of handwashing and other sanitary behavior. I’m confident these changes will decrease our exposure to the coronavirus, and as a result, limit the spread to our vulnerable friends and family and subsequently, within our greater community.

Every apartment is a microcosm of the entire country. Health is collective; when it comes to infectious disease, excuses like “I’m not in a high-risk demographic” or “I rarely get sick” are dangerous when translated into a refusal to be inconvenienced by changes in routine. While a coordinated government response is crucial, everyday decisions to limit the spread of disease — the bulk of which are done privately and voluntarily — are equally critical. Having plans in place in co-living situations and having socially intimidating conversations sooner rather than later is crucial to mitigate the higher risks associated with our city’s close quarters.