Along Turk Street in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district, homeless people form shanty towns from dirt-caked tents, busted shopping carts and miscellaneous trash. The smell of week-old piss permeates the crowded sidewalks they’ve conquered for the night, though their struggle to live in America’s tech mecca is far from over. Each block filled with their forgotten faces is a chilling reminder that my own stability is merely an illusion, and by the time I see the rainbow flag flying outside Aunt Charlie’s Lounge, the neighborhood’s oldest and only surviving gay bar, it’s a welcome sight. A sanctuary.

Of course, San Francisco was synonymous with gay culture long before the rainbow flag, designed in 1978 by SF native Gilbert Baker, gained international notoriety; it’s the land of Harvey Milk and honey for every queer person I know. Even as a proud New Yorker, I find that the city’s allure is ingrained in my gay-boy bones as deeply as my inexhaustible love for Judy Garland is. So when my boyfriend, who bounced around the Bay Area for 13 years in a previous life, invited me to join him on a weeklong trip to San Francisco recently, I, like Judy at Carnegie Hall, emphatically sang, “San Francisco, open your golden gate!”

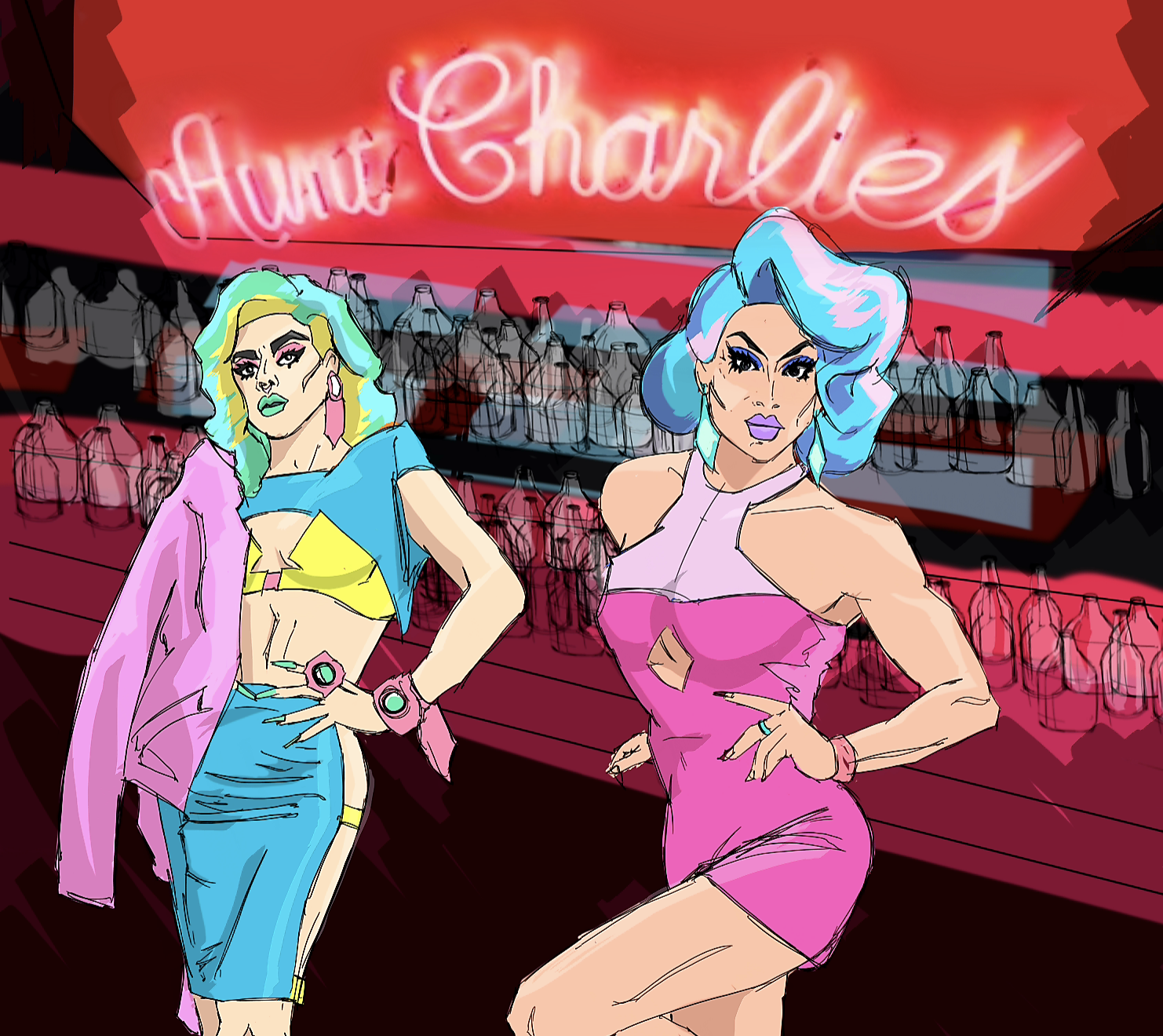

Vestiges of the city’s older gay ghettos are disappearing into tech start-ups and luxury condos. In spite of the city’s evolution, Aunt Charlie’s is a landmark that has persisted.

I was ready to rub elbows with the likes of Cleve Jones, visit haunts frequented by Allen Ginsberg and pay homage to my forefathers still lurking in seedy gay dive bars. When I mentioned this affinity for daddies and dives to my boyfriend’s old roommate, a local San Franciscan, he lamented that my Barbary Coast fantasia would soon be relegated to the footnotes of a history book. Vestiges of the city’s older gay ghettos are disappearing into tech start-ups and luxury condos. In spite of the city’s evolution, Aunt Charlie’s, he affirmed, is a landmark that has persisted. I had to go.

Upon entering, I’m greeted by a burly, bespectacled drag queen with smeared lipstick and a bedraggled wig who sits watch behind a tattered curtain. She’s of an indeterminate age, and the low lighting does her favors. The only line of defense between the people on Turk and the patrons inside is her as both hostess and bouncer.

Vintage porn of cherubic men with horse-hung cocks plays in a loop on the bar’s two video screens.

“It’s a $5 cover,” she grumbles in a husky baritone. I oblige, though from the look of the empty bar, it seems like I should be the one getting paid to enter. But I don’t make a fuss. She peers at me from over her ’70s-style wire-frame glasses and grins. “Have fun,” she says tenderly.

A worn wooden bar crowds one half of the room; sectional seating takes up the other. A walkway glides through them, leading to a small dance floor and a DJ booth, where Bus Station John, the lumberjack of a man behind the night’s revelry, is meticulously affixing panels of cheap silver tinsel to the walls. It’s Thursday, and on Thursdays, Charlie’s does disco, though 1920s jazz currently bubbles from the ceiling’s sound system while the room is transformed for the weekly party.

Vintage porn of cherubic men with horse-hung cocks plays on a loop on the bar’s two video screens, and I can’t help but wonder, as I always do while watching old adult films, how many of these baby-faced twinks survived the AIDS epidemic. Instant boner killer. Red Chinese lanterns dangle over bar stools alongside mobiles of Grace Jones album covers, and a few oversize tapestries depicting leather-bound daddies hang from the walls.

Aunt Charlie’s, which changed names from “Queen Mary” in 1987 when current owner Bill Erkelens bought the bar, is more historic relic than happening scene, a kitschy tourist stop in a famously seedy locale that harkens back to the days before the Castro and SOMA took over as San Francisco’s capitals of queer. Most importantly, it’s the Tenderloin’s final reminder of a boy-bar heyday. The Gangway, a mainstay that once held the title for longest continuously operating gay bar in the neighborhood, closed up shop last year and has turned into a kung-fu-inspired watering hole by the same owners of Kozy Kar on Polk Street. There aren’t any rumors of a gay bar opening up nearby anytime soon, though Nate Albee, an LGBT activist who helped save the Stud in 2016, has tried to rally a consortium of nightlife owners to reopen the Gangway in a new location. Albee’s plan has yet to materialize.

Of the seven current patrons, three appear to be straight women. One of the girls has dragged along her straight boyfriend. An older gentleman, presumably gay, sits alone. My boyfriend and I, tourists from New York City, round out the crowd. One of the women takes out her cell phone to snap a picture of the scene, but the lumberjack barrels over and shouts, “No phones allowed!” over a tinny piano solo. She obliges.

I order a $5 Sierra Nevada, considerably cheaper than drinks in the Castro, and grab a seat in front of one of the Tom of Finland fantasies hanging above me. With the absence of smartphone screens lighting the bar, and prices reminiscent of 1995, it’s almost like I’ve taken a time machine to the 20th century.

I close my eyes and try to lose myself in the music, hoping the heavy synth will magically transport me to a time when this room pulsed at the heart of San Francisco’s queer culture.

The decorations are given their finishing touches while the DJ begins spinning “I’m Still Here,” a Stephen Sondheim classic from the musical Follies. The song, a cabaret favorite often interpreted by Broadway divas in their twilight years, is played six times in succession. Each time it’s sung by a different icon: Elaine Paige, Elaine Stritch and Eartha Kitt, to name a few.

Good times and bum times, I’ve seen them all, and my dear — I’m still here.

Each voice warbles with the wisdom of a jaded warrior as they wax lovingly about the unstable realities of showbiz.

I got through all of last year…and I’m here!

Of the three chanteuses listed, only Elaine Paige survives.

The music turns from Sondheim to ’70s tunes, and the room fills with a hodgepodge of hipsters and older gay men. The tinsel almost effectively mimics a disco ball, and I feel like an actor playing the token gay character in an immersive community-theater production of an Armistead Maupin spin-off—Tales of the (Old) City.

As disco blares over the sound system, I close my eyes and try to lose myself in the music, hoping the heavy synth will magically transport me to a time when this room pulsed at the heart of San Francisco’s queer culture; before the city was settled by the tech industry; before love was love was love; before AIDS killed an entire generation; and when mustachioed men danced carelessly to the songs of Donna Summer in dives that became their sanctuaries from a world that didn’t accept them. But when I open my eyes, I’m the only one dancing.