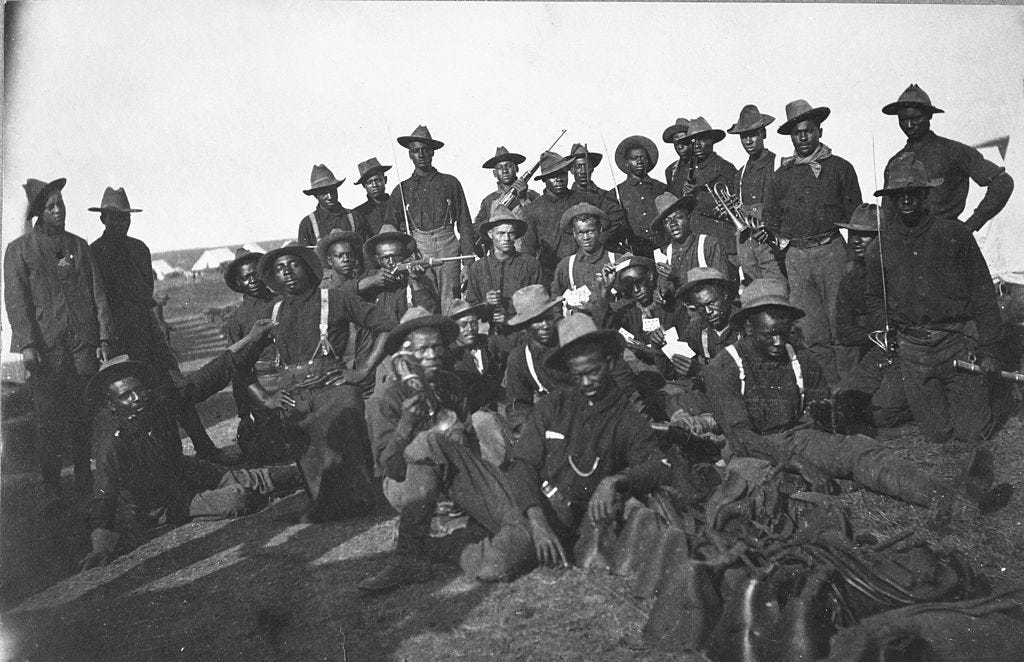

The history of California is filled with Blackness. Melanin is woven into the state’s fabric, from the Black founding families of Los Angeles to the buffalo soldiers who patrolled the state’s frontier. Long before the Black Lives Matter movement or the Black Panther Party, Black Californians led the way in fighting for equality and pushing the state to become progressive.

But most Californians are unaware of this history and the reality the state California didn’t just happen to become the so-called land of dreams — or the beacon of progressive values — organically; it was the result of minority groups organizing and challenging the status quo since the state’s inception.

Acknowledging how little most Californians know about the history of Black people in their state, the San Francisco Unified School District recently passed a resolution to include Black studies as part of its K-12 curriculum starting in the 2022–2023 school year. This curriculum, funded with $15 million and meant for all age levels, will introduce students to the concept of race, systemic racism and the contributions Black people have made to the country and the state.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

“The broader impact of African innovations such as math, science, engineering, sea exploration and astrology that informed much of Western civilization has never been sufficiently taught to students in traditional public schools,” said SF Board of Education commissioner Stevon Cook in a press release.

This move by the SF school district is an important step to increase local understanding of how Black people shaped California history. Understanding the past not only pays tribute to our ancestors’ fight but also helps inform how we can better deal with lingering injustices today, from continued segregated education to racist economic and housing policies.

Understanding the past not only pays tribute to our ancestors’ fight but also helps inform how we can better deal with lingering injustices today.

The truth is that the liberal and diverse California we treasure today didn’t happen because white people decided to play nice. It’s because marginalized groups chose to fight for their rights. As a former territory that heavily considered becoming a slave state, it was also a place where Black people could once not testify in court, segregation was legal, and systemic injustice took place routinely.

The route to change all started with early Black migrants who came west.

It started with Black California.

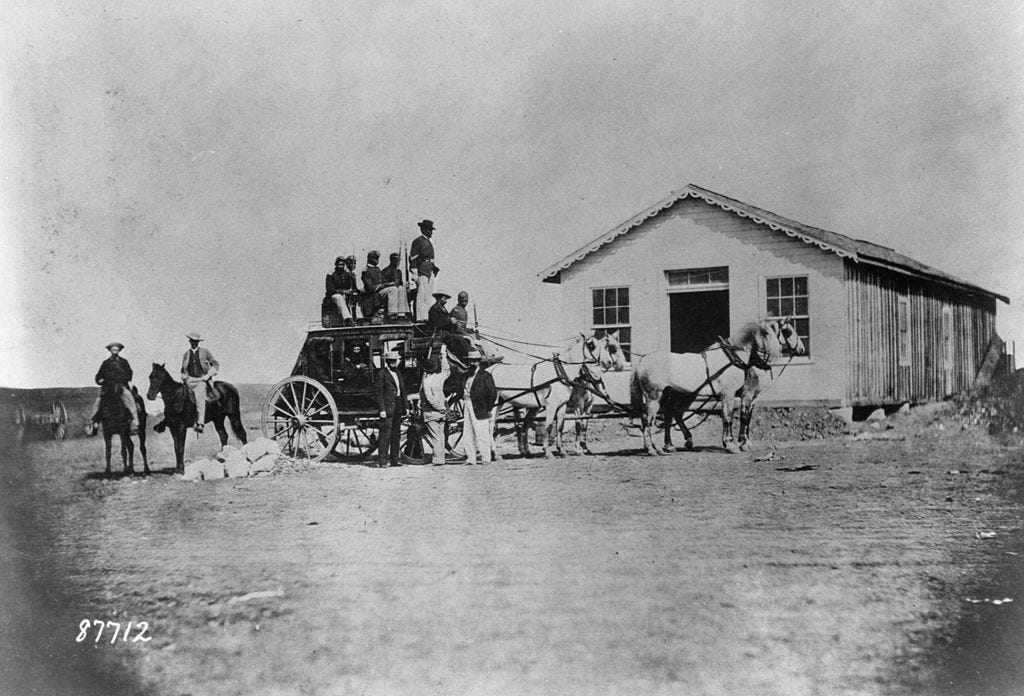

For opportunities, they came west

Like most West Coast stories, the story of Black California began with the search for opportunity. And the Gold Rush offered an abundance of it. As noted by researcher Gabriel Barrett-Jackson, Black migrants came to California from across the country during this Western boom in the mid 1800s in search of jobs, better economic promises, and freedom from racial tension.

In the lead up to the land going from wild western frontier to state in 1850, politicians had heated debates about whether to allow slavery. While they eventually decided to outlaw it, there were still residents and legislators that called for Black people to be banned entirely, including California’s first governor Peter Burnett.

“It could be no favor, and no kindness, to permit [free blacks] to settle in the State,” he said, according to History.com. “While it would be a most serious injury to us….Had they been born here, and had acquired rights in consequence, I should not recommend any measures to expel them…the object is to keep them out.”

Those intentions obviously didn’t pan out. And African Americans arriving in California during the Gold Rush found pretty good living and working conditions — at least compared with where they came from, says Stacey Smith, a history professor at Oregon State University who researches Black migration to the West Coast during the 19th century. “People who performed domestic work like cooking, housekeeping, hair services, and laundry were quite valued in the early years of the gold rush,” Smith says.

The opportunities weren’t just domestic work; some residents — like Mary Ellen Pleasant, a Black woman who was a Gold Rush-era millionaire and an abolitionist — were successful business owners.

California’s new Black residents came from all walks of life, but one group in particular would be key in the socio-political successes of the state: the Black middle class.

“Getting to California was expensive and required most Black migrants to be at least financially secure enough to afford the journey West,” says Smith. With a middle-class status came education, knowledge of how the courts worked, and the economic ability to fight oppressive policies, Smith notes. It was this demographic in San Francisco that played a vital role in the economic and cultural development of the Bay Area.

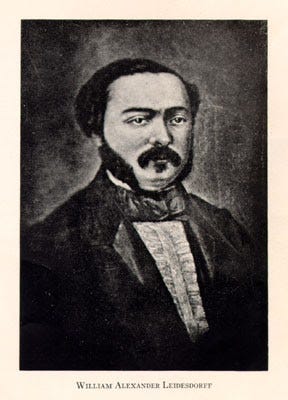

Black Bay Area residents shaped their communities in the 1800s with storefronts. In fact, nothing was more Bay Area than a Black business owner. It was a Black immigrant named William Leidesdorff who constructed and owned the city’s first hotel, named the City Hotel. Educated and wealthy Black residents established newspapers and became entrepreneurs.

The Bay Area was also a region of Black activism. Oakland housed many local activists, like the Flood family. Elizabeth Scott Flood and her daughter, Lydia, fought tirelessly for education and women’s rights. The Bay was also the home of Jeremiah B. Sanderson, an activist and educator who established a Black school in Sacramento and was a well-respected teacher in Stockton.

Indeed, Black residents in the West had better job and economic prospects than other places in the country at the time — but they remained reliant on the good graces of the white community. This motivated many Black communities in California, especially in the Bay Area, to fight against oppression.

The activists that paved the way

In 1850, the U.S. Census recorded 962 Black people in California out of a population of 92,597. Although the population would grow over the next 10 years, Black California remained small at only 1% of the state’s population. However, the community’s voice was loud, and it had money — at least compared to other parts of the country. Especially in San Francisco.

In his 1987 book The Black West, historian William Loren Katz estimates Gold Rush-era Black California’s wealth at “$2 million in assets,” which today would equal more than $60 million. Katz goes on to say that “more than half of this wealth was located in San Francisco.” In a time when people were literally panning for gold in hopes of making it big, Black California was building wealth through services and business. This was a community that had the time and money to fight for their rights.

And their victories were monumental.

In 1872, a San Francisco principal, Noah Flood, denied the application of student Mary Frances Ward to Broadway Grammar School. The reason? She was Black. Her parents were not pleased with his racist reasoning and sued the principal in a case called Ward v. Flood. In 1874, the California Supreme Court decided that because there were “colored schools” that Mary could attend, no harm was done. But a year later, San Francisco’s schools changed.

In 1875, Black San Francisco residents won their battle to integrate schools. As noted in an article by historian Alfred S. Broussard, this change, championed by influential white residents, was because “the segregated school was more expensive to operate on a per pupil basis than were the larger white institutions.”

‘Early African Americans in California were preoccupied with equal rights, with changing the laws and opening up California as a society.’

However, the move also demonstrated a crucial social shift, and that credit belongs to the Black community. Black people had made allies to support their cause. It was this allyship and civil rights advocacy work from the Black community to connect with privileged white people that led to integration. In short, it was not a simple matter of economics. When white people do not want to interact with Black people, they will happily spend money to keep the socio-economic distance, as demonstrated by the prevalence of segregation, redlining, and housing restrictions. The integration of San Francisco’s schools is a good example of demonstrating how the West wasn’t becoming progressive because it was less racist but because many in the Black community with resources fought for equality.

“From the very beginning, there’s been this presence of Black people that have influenced the state,” says Susan Anderson, a history curator and program manager at the California African American Museum and author of the upcoming book African Americans and the California Dream. “Early African Americans in California were preoccupied with equal rights, with changing the laws and opening up California as a society.”

When California entered the union as a free state in 1850, white settlers rushed to establish laws that created an unequal society. The 1854 state legislature passed the California Practice Act, which outlawed Black residents from serving as witnesses in court against a white person. This law became a catalyst for Black activism in the Bay and across the state.

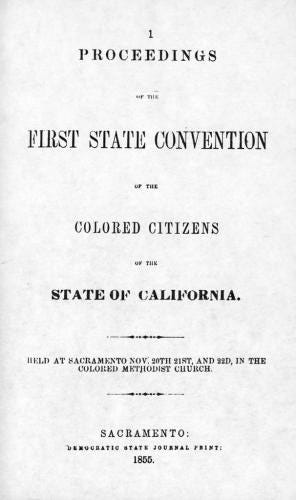

As noted in The Black West, it was this law that motivated Black San Franciscans to organize a Franchise League, a political group aimed at fighting injustice. San Franciscans also took part in statewide conventions called the Conventions of Colored Citizens that adamantly petitioned against the law and other injustices.

“African Americans in California history have helped transform the civic culture in the state because the state of California, along with other Western states, began in social and racial injustice,” says Anderson.

And in the Bay Area? That is where many fights for justice were won.

After being thrown off of a San Francisco streetcar in 1863, Charlotte Brown, a Black woman, won a series of lawsuits against the city’s streetcar companies for discrimination. In another example, Mary Ellen Pleasant, a Black businesswoman, also successfully sued a streetcar company three years later when they denied her access. According to the ACLU of Northern California, Pleasant’s case eventually led to the Supreme Court of California ruling that segregation on streetcars was illegal.

These victories came in the years during and after the Civil War in the 1860s. As the nation fought over the right of white people to own slaves, Black women were winning the right for their people to access public transportation in the Bay Area.

These victories in education and public transit were monumental, but of course, Black Californians and Bay Area residents continued to face housing, employment, and other types of discrimination.

The fight for equal rights is not a one-step process. We often frame civil rights victories as big, such as how the right to vote can change the experiences of a community. The reality is that change takes place in small steps over time. The rights that Black California activists fought for over the following 100 years were not so different from that of early residents. However, it was the victories of the past that left their mark, that showed that in the Bay Area, you could fight and win. The Black Californians of the 1800s laid the foundation for future activists. The early 1900s were filled with Black Bay Area activism and the establishment of new political organizations aimed at the improvement of Black lives.

When faced with the budding presence of the Oakland Ku Klux Klan, the Black community pushed back. The early 1900s also saw the establishment of a local NAACP branch, which played a role in fighting for equal rights. By the 1960s, the activism that had begun almost 100 years prior was in full bloom. It is no surprise that the Bay Area became the birthplace of the Black Panther Party; the fire was already there.

For too long, the narrative has been that Black people were given rights rather than the reality: that they fought for them.

The importance of remembering

You may not have known this history about California or San Francisco. And that is a problem, whether you grew up here or if you are new here. Knowing about past issues like the desegregation of schools and streetcars is important for understanding how these issues of inequality have always been at the core of the Californian experience. And it shows howBlack people have been the drivers of social change.

For too long, the narrative has been that Black people were given rights rather than the reality: that they fought for them. It was the work of early activists that began the process of breaking down barriers and offering opportunities to newcomers in the years to come. This part of Californian history is essential. However, accessing it has not always been easy. Luckily, the San Francisco Unified School District agreed this needed to change.

San Francisco students will finally begin to learn about the contributions of Black residents. John William Templeton, curator of the California African American Freedom Trial —a collection of 6,000 sites in 58 counties— says he is happy with the school board’s decision.

“Unless you include this information at every level of education and every level of public policy, you are not going to change anything,” said Templeton, who has taught California’s Black history for nearly 30 years. He is right.

Until cities teach this history, the modern push for equal rights loses its historical precedent. After all, concepts like Black Lives Matter are not new. They are ideals carried on from generations of Black activists demanding that the oppression, violence, and hate toward their community ends.

By teaching the history of Black California, students will gain a critical understanding of history and how, as a nation, we have often failed to address inequalities. Perhaps it will give the younger generations an idea of how to solve these inequalities. San Francisco’s move to integrate the stories of Black people into the narrative of the city will help assure the contributions of early migrants are remembered. If only the rest of the state — and the country — would follow suit.

We must remember that the fight for equality did not begin with the death of George Floyd or Breonna Taylor. This fight is interwoven into the history of Black America, one that is essential for local communities to remember and center.

Note of acknowledgment: A deep thanks to the San Francisco African American Historical and Cultural Society, which connected me with resources on Black history, enabling me to write this piece.