If you’re a resident of Oakland or the greater Bay Area, you most likely have an opinion about the recent decision to move the Raiders from Oakland to Las Vegas. Whether or not you care about the team’s eventual departure, chances are you’ve helped fund the Raiders’ stay in Oakland—and have absolutely nothing to show for it.

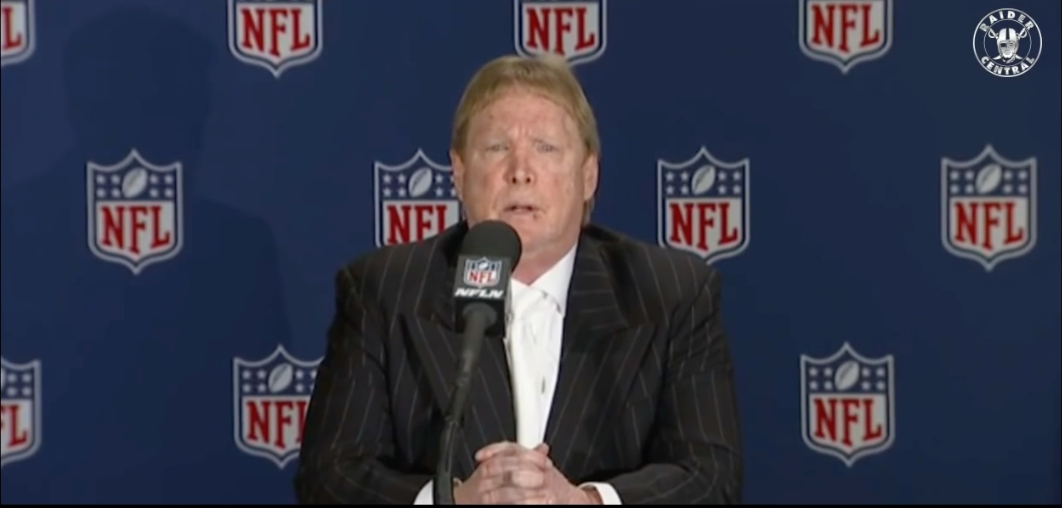

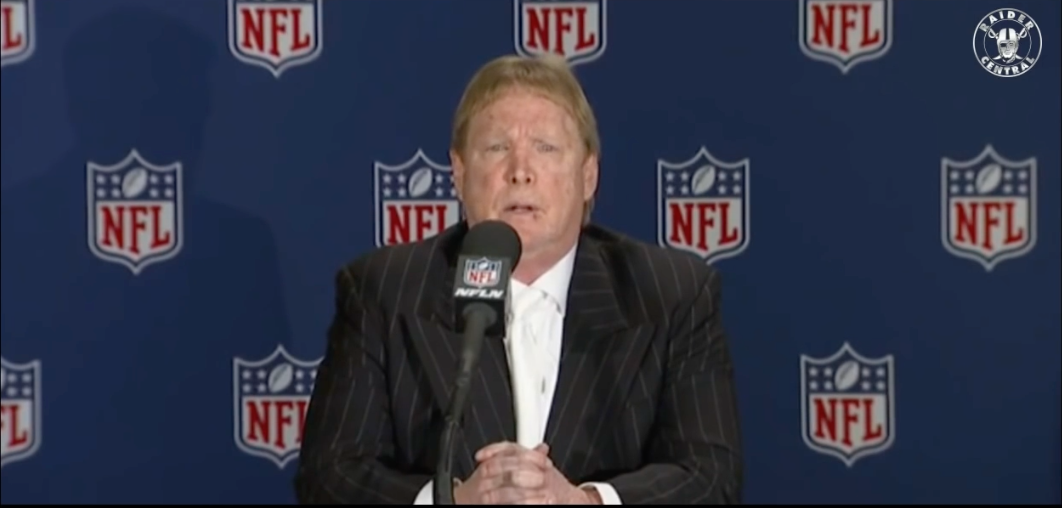

Oakland still has $95 million in debt remaining from the 1995 Raiders stadium renovations that team owner Mark Davis lobbied the city to complete, threatening not to bring the team back from Los Angeles if they didn’t.

And that’s not the worst of it.

Oakland even prioritized funding the Raiders over their own police department. In 2011, when the city was still bearing the brunt of the Great Recession, Oakland faced a budget deficit of $32 million. That year, Oakland suffered over 100 homicides and had a homicide rate five times the national average, surpassing cities like Chicago in terms of murder rate per capita. Despite this, 138 police officers were fired, while $17 million was funneled from taxpayers to the NFL to pay for maintenance costs related to season games.

Major League sports arenas are funded in a similar fashion as public parks are, except you get to enjoy public parks for free, as they’re collectively owned by you, the citizen. This is not the case with sports arenas.

Oakland city leaders bent over backward to accommodate the Raiders, and it didn’t matter. At the first sign of a more lucrative deal, they left Oakland high and dry for a jackpot worth nearly $2 billion in Las Vegas, $750 million of which will come directly from Las Vegas taxpayers.

The involvement of taxpayer money, which would better serve the population of Las Vegas if it were to be spent on literally anything else, raises serious questions about the validity of private ownership in relation to Major League sports teams around the country.

Major League sports arenas are funded in a similar fashion as public parks are, except you get to enjoy public parks for free, as they’re collectively owned by you, the citizen. This is not the case with sports arenas. One still has to pay for overpriced tickets, parking and marked-up food and drinks—all for the benefit of the NFL and its sponsors.

It doesn’t necessarily have to be that way. Legal scholar Sam Karimzadeh argued that there is a strong case that eminent-domain laws entitle cities like Oakland to take sports teams back for the people.

I agree. If citizens are the ones who fund the sports teams, they should see the benefit of the team’s presence. Instead of lining the pockets of billionaire owners like Mark Davis, the capital generated by major sporting events could be used to fix potholes (especially in Oakland’s case); maintain public parks; fund other public-works projects, emergency services, public education and local health clinics; balance the budget; or invest in better public transportation. Or it could even saved in the form of a rainy-day fund in the event that Trump makes good on his threat to withhold federal funds from sanctuary cities.

All we currently get is added strain on public infrastructure and other essential civic services, while parasitic billionaires find ways to suck even more blood from the cities that host the teams.

If Green Bay can publicly own their team, why can’t we do something similar in the San Francisco Bay?