In response to demonstrations protesting the killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and countless other Black Americans, cities across the country have implemented historic curfew orders this week.

The orders, officials say, are intended to curb violence and property destruction. But curfews have long been a mechanism for controlling people of color, especially Black people.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

While curfews for certain races or parts of towns have peppered the region’s history, the current Bay Area-wide curfews appear to be unprecedented. Oakland, San Francisco, San Jose — and essentially every other major city — put curfews in place this week.

Thousands of demonstrators have protested those curfews, sitting-in after permitted hours. In Oakland, Wednesday’s demonstration was called “F*** Your Curfew.” Now, San Francisco and San Jose’s curfew is set to end Thursday morning at 5 a.m. and Alameda County’s on Friday morning.

Just before announcing a curfew on June 1 that would run from 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. until further notice, Oakland Mayor Libby Schaff acknowledged the painful history of curfews.

“Curfews have been used as a form of government oppression and racism,” Schaff said at a press conference on Monday. But then she put one in place anyway.

Indeed, the use of curfews to suppress freedom of Black people stems from the 18th and 19th centuries, when they were employed to prevent slaves from gathering at night and inciting mass rebellions against slave masters. Later, during the Jim Crow era, notices prohibiting Black people from inhabiting entire towns after sunset effectively created what’s known as “sundown towns” — all-white cities that segregated the country.

In Northern California, curfews date back to 1942, when they were implemented as a precursor to Japanese internment. Prior to being relocated to camps, Japanese Americans were forced to stay at home after sundown. German and Italian immigrants were also included in the wartime curfew. Those who violated the order faced severe punishment: one year’s imprisonment.

Since then, curfews have been employed mostly to quell the rage of protesters. During the civil rights movement, cities across the country implemented curfews in order to control protests that had grown unruly. After the murder of Rodney King, Los Angeles implemented a citywide curfew.

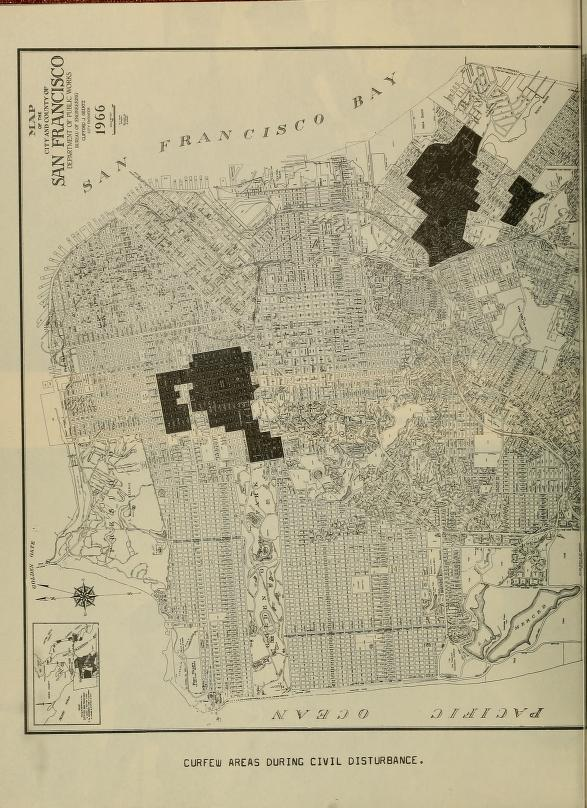

The last time San Francisco issued a curfew order in 1966, the city had erupted in protest after a police officer fatally shot a Black teenager. Sixteen-year-old Matthew Johnson had been driving a stolen car with two friends when a police officer chased after him and fired his weapon, killing Johnson. Mayor John F. Shelley responded to the uprising by calling in the National Guard and ordering a curfew in predominantly Black neighborhoods throughout the city — Bayview-Hunters Point and a portion of the Haight and the Fillmore.

“The similarities just show how little has changed,” said Sara Kershnar, the acting executive director of the National Lawyers Guild in San Francisco, which provides legal defense during protests and mass uprisings.

“Curfews are meant to reassert the power of the state,” Kershnar said.

Because people often work during the day, putting a time limit on a demonstration can effectively shut it down, she explained. Curfews also work by making it easier for the police to arrest someone. Typically, police are required to suspect illegal activity in order to arrest someone. With a curfew, simply being on the street is reason enough.

“Curfews do give law enforcement incredible latitude to arrest,” said Scott Cummings, a professor at the University of Southern California Law School who has studied the relationship between social movements and the law. “It can be an incredible invitation to an abuse of power, because now people can be swept off the street without any reason whatsoever, simply because they’re on the street after the curfew, even if they’re exercising legitimate rights and engaged in important political activity.”

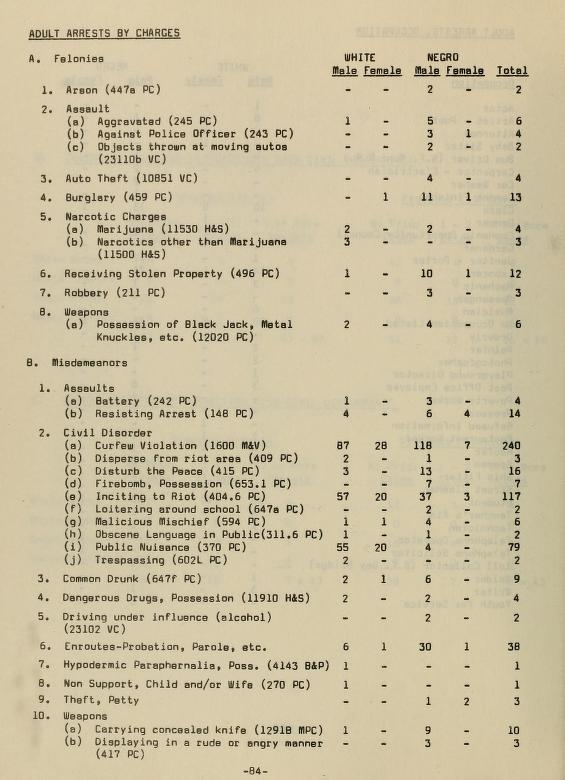

The increased capacity leaves room for biased enforcement of minor violations. In the five days that the 1966 Bayview-Hunters Point Uprising lasted, half of the 900 arrests were for “civil disturbance” — behaviors like “creating a public nuisance” or “inciting to riot.” And 240 arrests alone were for violating curfew. As a comparison, the police made only 13 arrests for burglary during the demonstrations.

When a government cracks down on protest and property damage but doesn’t address the root cause of both, it sends a clear message about its priorities — law and order over equity.

Curfews are legally justified only when the police deem that the threat to public safety can most narrowly be addressed by one. Now, given the state of emergency already declared due to Covid-19, it is easier for cities to declare comprehensive curfew orders, Kershnar said.

“This is a very powerful tool against freedom of speech in the form of the right to assemble and express dissent with the government,” she added.

Though the curfew is intended to target protesters, there could also be unwitting victims. Unhoused people, for example, have no choice but to be on the street. Shelters in the Bay Area are notoriously full, a problem only exacerbated by the global pandemic Covid-19. Though the order in Alameda County exempts unhoused people from arrest, this is no guarantee that people would be saved from harassment. The same goes for essential workers returning or going to work.

“Blanket closures of all public spaces gives police unfettered discretion, which has shown to lead to selective biased enforcement, and high potential for the exact type of racialized abuses that are being protested,” the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Northern California said in a statement. The ACLU is considering mounting a legal case against the curfews.

Since the curfew began, protesters have been arrested and detained for violating curfew in cities throughout the Bay Area, leading to an outcry in opposition to the curfew. In San Francisco, a small group of protesters were arrested for curfew violations on Wednesday night, but in Oakland, police stayed away from a peaceful protest against the curfew that went on until after midnight.

For many, the bottom line is as much about First Amendment rights as it is about the insufficient government response to systemic oppression. When a government cracks down on protest and property damage but doesn’t address the root cause of both, it sends a clear message about its priorities — law and order over equity.

“Rather than resolve what’s making people fed up, the state reasserts control by protecting the things that as a nation we prioritize like property over human life,” Kershnar said.