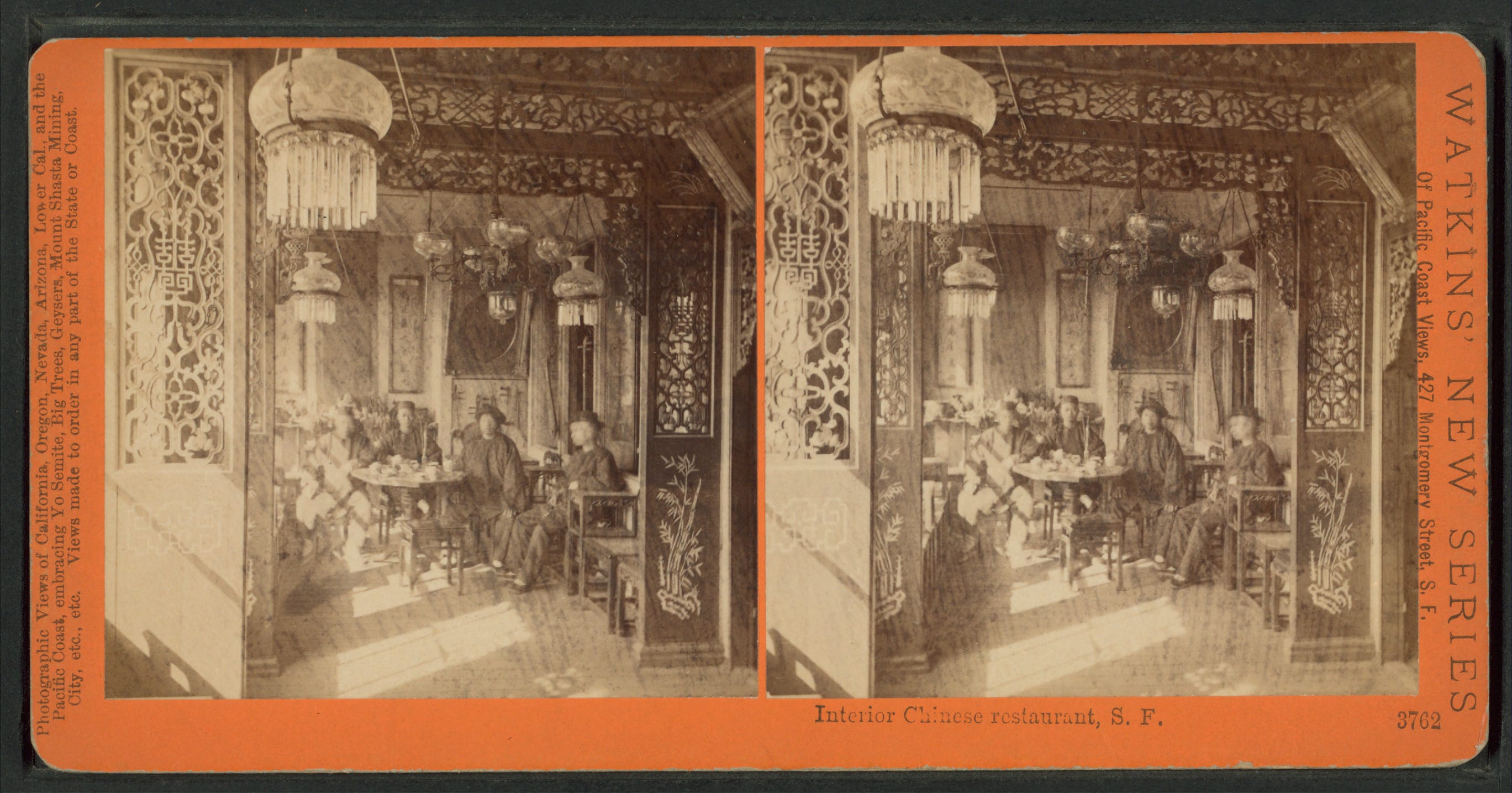

When most people think of San Francisco’s Chinatown, they probably think of the famous Dragon Gate. They also might imagine iconic restaurants like Z & Y Bistro or the more modern, Michelin-starred Mister Jiu’s. Perhaps it’s the tourist shops they recall — or the tiny but famous Fortune Cookie Factory, where visitors watch the cookies contort into their signature shape through specialized machinery. While these spots may be the most well-known to outsiders, the neighborhood is full of hundreds of other businesses that aren’t as eye-catching or distinguishable, sporting their names in Chinese characters. Their goods and services, however, speak to the living legacy of Chinatown as an actual Chinatown, not just a tourist destination.

There’s been a lot of talk recently about Chinatown’s survival, or at least the survival of many of its businesses due to the Covid-19 pandemic, though much of the same debate was underway pre-pandemic as I detailed in 2015. Most news articles compellingly and accurately focus on the human factor: how many of these businesses and especially restaurants have been family-owned and proudly passed down through the generations and how much they are icons for the Bay Area’s Chinese American population. However, there is another key aspect and one unique to Chinatown — the architectural heritage of Chinatown is distinct, and its survival is tied to the survival of Chinese American businesses.

Chinatown occupies an interestingly central place — geographically and otherwise — in San Francisco. It’s rich with history and cultural importance to this day, yet it’s often inaccurately portrayed as just a place for tourists to check off on a list. The neighborhood is fully organic in its urban form with fewer modifications than much of the city. In fact, it’s arguably the least changed of all San Francisco neighborhoods — not simply in terms of architecture but also the continuity of the types of businesses and their role in the community.

When I moved to Chinatown in 1997, I was immediately captivated by its spirit. The more I learn about Chinatown, the more evident this compact neighborhood’s amazing legacy becomes and how crucial it has been for the history of Chinese Americans. The dependence of Chinatown on tourism and especially restaurants has been hit hard by Covid-19, and the increasing, alarming, racist attacks on Asian Americans are also a concern. For Chinatown to survive, it will need its businesses to bounce back; that is crucial because of the depth and scope of history here.

With the number of businesses at risk, my fear is that if Chinese-centric businesses are lost, so too will be the innate character. Without them, you would simply have some curious chinoiserie (of a Chinese-inspired but Westernized or stylized aesthetic) ornamentation: What makes Chinatown’s architecture so vibrant is its living character. Elderly aunties clamoring to get the freshest fish, teens going to get their hair done — even the tourists and the kitschy gift shops make it alive. Besides that, a lot of people still live here: Chinatown, though notorious for its single-room occupancy residential hotels and their grimy conditions, remains one of the most affordable parts of the city. Many Chinese immigrants still come here like generations before have, seeking a better future, and Chinatown is a necessary gateway for that. We have seen already in a few decades how much the Mission has changed; I don’t want to see that happen here as well.

While most Chinese Americans live elsewhere in the Bay Area now, many still come to Chinatown to shop, maybe to get a haircut, and, yes, to dine at its many restaurants. I often read foodie articles claiming that the better Chinese restaurants are in the Inner Sunset and elsewhere now, not Chinatown, but it’s rather subjective what “better” means: Is it what is cutting edge for the foodies, or is it what harkens back to the authenticity of Hong Kong for someone who grew up there? For the latter, Chinatown probably cannot be beaten. And certainly, if you need some sea cucumber or rare ginseng yourself, it’s the place to shop.

To get a sense of the importance of the neighborhood and its unique architecture, we need to dive into history.

The first mayor of San Francisco, John Geary, stood in Portsmouth Square on August 28, 1850, and announced a welcoming of 300 Chinese workers, apparently all men, to the city. This speech marked the first public notice of Chinese immigrants arriving in northern California for work, though these 300 likely weren’t actually the first to arrive. Most came from the southern Chinese province of Guangdong seeking work in various industries spurred by the growth of the city, like the building of railroads and digging for gold. A mere year later, more than 12,000 Chinese men lived in San Francisco (fewer than 10 women were recorded on a city census).

These Chinese immigrants settled near Portsmouth Square, now a blocklong park in the heart of Chinatown. They probably didn’t land there because the mayor welcomed them; inversely, the mayor probably welcomed them there because Chinese immigrants were already settling in the area by the time of his speech. From Kearny Street east to Stockton, from Bush Street north to Broadway, and especially along Dupont Street (now Grant Avenue), Chinese people settled, and this neighborhood was legally decreed the only real estate that Chinese immigrants could purchase and could pass down to heirs.

This was crucial because it meant Chinatown had legal, political, and economic reasons to remain primarily occupied by Chinese immigrants. It wasn’t happenstance that most Chinese immigrants chose to live here even after these draconian laws were repealed, as some inherited property from relatives and others sought assistance from the Chinese Benevolent Associations (or Chinese Six Companies) that represented six districts in Guangdong from which these immigrants hailed. In Guangdong, the Six Companies had lineages going back centuries and held a sociopolitical power, but in the United States, they were organized representations of collective social interest.

These associations, such as the Mou Young Fong or Yan Wo Benevolent Associations, exist in Chinatown to this day and have played a variety of roles since their inception, originally helping new immigrants find work and housing but now sponsoring youth groups and cultural events.

While Chinese immigrants were often victims of racism, many were financially successful by opening businesses despite Chinatown achieving the stereotype as a locus of crime and intrigue.

The infamous 1906 earthquake and its resulting fires changed things for Chinatown as it did for much of San Francisco. Fire departments ignored Chinatown and concentrated on the wealthy, white, enclave of Nob Hill instead, even going as far as to dynamite Chinatown buildings to create a firewall against the flames. In the wake of this destruction, a noted architect at the time, Daniel Burnham, drew up concepts to eliminate Chinatown, relocate Chinese people to Hunter’s Point, and rebuild the neighborhood as basically an extension of Nob Hill. However, astute Chinese leaders were able to plead that Chinatown contributed mightily to the economy and provided services such as laundromats that would no longer be accessible to San Francisco’s elite if they were moved to Hunter’s Point.

Chinatown was saved.

The problem was, between the earthquake, fires, and overzealous fire department, there was simply little left. The Chinatown of the 1850s to 1900s certainly had grown some Chinese influence in 50 years’ time, but its architecture was mostly the traditional Victorian residential and commercial timber frame of a low quality.

Though Chinese in populace, its aesthetics and urbanism were overall Western.

Enter Look Tin Eli, an American-born Chinese entrepreneur who, in another time, might well have become mayor of San Francisco. He was basically the de facto mayor of Chinatown as well as the manager of the successful Sing Chong Bazaar and later an important banker. Look Tin Eli envisioned a more Chinese Chinatown. He hired architect T. Paterson Ross and engineer A.W. Burgren to complete the task. The first building to get their attention was the Sing Chong itself; they placed a pagoda atop it. Pagodas are traditionally sacred architecture, temple forms that derived originally from Indian stupas but in China became towers crafted of wood, stone, or other construction.

This building and its neighboring Sing Fat Bazaar still exist and still sport their pagodas at the intersection of Grant and California.

Ross and Burgren brought a chinoiserie approach to much of Chinatown, rebuilding with an American sensibility toward use and application. They coated buildings with Chinese-themed ornamentation atop of Western construction techniques and floorplans (which today might be termed façadism). However, the architects were informed mostly by historical drawings and diagrams of often sacred Chinese architecture. Though born in America, Look Tin Eli had lived in China for some time and traveled there for business, but the images he or others gave the designers offered limited insight to contemporary Chinese urbanism. This is especially important to note because it explains why even commercial buildings in Chinatown boast elements of temple architecture — these were simply the references Ross and Burgren had.

The redesign of Chinatown was a success and became a tourist attraction. Meanwhile, the early to mid-1900s brought more Chinese immigrants arriving elsewhere in the United States, and other growing Chinatowns looked to the redesign of San Francisco’s for inspiration, so this aesthetic spread. It was this mesh of pagodas, overhanging hip roofs (wǔdiàndǐng, 庑殿顶), dragon gates (paifang, 牌坊) and que (闕) towers, lanterns, and red- and gold-themed aesthetics which not only spread to other Chinatowns but became the go-to look for countless American Chinese restaurants as well. And it all began in San Francisco’s Chinatown — the handiwork of American designers and a Chinese American businessman.

Chinatown businesses have long favored prominent signage, often in the form of awnings, to include both Chinese script and English. Grant Avenue became the central tourist, restaurant, and dry goods thoroughfare — evolving from the bazaar era of Sing Chong and Sing Fat there — while Stockton Street became the place to shop for groceries. Restaurants vary from quick sit-down cafés to Hong Kong-style dim sum to elaborate banquet halls. The famous Fortune Cookie Factory in Chinatown helped cement the fortune cookie as an icon of Chinese American cuisine, though its origin one way or the other tracks back to a Japanese confection, the tsujiura senbei (辻占煎餅). It is argued that today’s fortune cookie was invented either here in Chinatown or possibly in Los Angeles.

Much of this ambiance has been retained in Chinatown even today, and its tourism value has been long recognized. However, this architecture was — from its very origins with Look Tin Eli — tied to commerce, and it is the Chinese restaurants, gift shops, grocers, and other businesses that add their contemporary nuances to the architecture. While the gift shops and restaurants may be what stand out to tourists, there are also hair salons, bakeries, greengrocers, fishmongers, printers, lawyers, accountants, and other businesses catering primarily to Chinese Americans even now.

The aforementioned dried seafood cannot be easily sought in most of America while the printers print the menus of most Chinese restaurants in San Francisco. Bookshops specializing in Chinese literature, the benevolent associations — all these are integral still to Chinese American society. Today, there is a private Chinese-language high school and even a Chinese hospital in Chinatown as well as branches of numerous Chinese banks. While the foodies may say you go elsewhere for the most exciting or novel takes on Chinese cuisine, the reality is Chinatown remains very much a workaday window to China.

Yet a variety of factors — gentrification, competing demands for property, Chinese Americans moving further afield in the Bay Area, and now Covid-19 — have presented serious challenges for Chinatown and its future as such.

An understanding of the intrinsic worth of Chinatown for the Chinese community needs to be fostered so non-Chinese Americans realize that this isn’t just a tourist destination but part of a whole community’s cultural heritage. And in the immediate present, many businesses and residents need help. In good news, the city recently passed a $1.9 million relief package for the neighborhood. And residents can get directly involved, too, through programs like the Chinatown Community Development Center’s Feed and Fuel Chinatown initiative. More than anything, supporting Chinatown businesses as the city opens up from quarantine will be crucial.

There’s a lot that remains in Chinatown that I think Look Tin Eli would readily recognize if he walked through the Dragon Gate today. We must make sure that doesn’t change for failing to support the businesses that bring so much vibrancy to the storied buildings of the neighborhood.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.