Whether you’ve walked, driven or pedaled through San Francisco, you’ve likely noticed its glittering streets and sidewalks. No, this isn’t leftover Pride paraphernalia—those are so-called street diamonds.

Street diamonds, while they may come in a variety of shades, sizes and colors, are typically small and appear seemingly overnight in large clumps. While they’re not necessarily dangerous to the touch, cyclists fear their tire-slashing prowess. Car owners, on the other hand, look at the glassy outcrops and think, “Maybe I shouldn’t park here after all.”

As much as I’d like to believe that street diamonds are a marvelous precious mineral bursting forth from the earth like a bedazzled drag queen leaving her apartment for Sunday Funday brunch, they’re just glass. Broken glass. From auto burglaries, most often, but sometimes also from a broken bottle on the sidewalk or debris trailing from a recycling truck.

Having spent years avoiding it on sidewalks, picking it out of my bicycle tires and cleaning it out of the passenger side of my car, I decided to investigate what exactly this glass is that I keep seeing — and how big of a problem it really is.

What is it?

Much of the glass you find along roadways is from cars — what’s called “safety glass.” Safety glass is any kind of glass that’s been toughened up in some way so that it’s less likely to break. There are two main types* of safety glass you’ll find out there: tempered glass, which breaks into very small pieces when broken, and laminated glass, which is designed to stay together even if it’s broken.

The latter first began being incorporated into cars as early as the 1920s. (The first time it was offered standardly in a car was in the 1936 Rickenbacker.) To make this kind of safety glass, one or two layers of glass are sandwiched between layers of thin, flexible plastic film (PVB, or polyvinyl butyral). That plastic film keeps the glass intact in the event of a direct impact. This type of glass is used mainly in car windshields.

Tempered safety glass is created through a process of heating it, then swiftly cooling it down. This process can increase its strength against breakage up to 10 times compared to normal glass. When it does break, it doesn’t split into dagger-like shards but instead splits into small, almost pebble-like chunks.

As you might surmise, laminated glass is stronger — it’s (part of the reason) why you very rarely hear about people being ejected out of the front windshield in serious auto accidents. Cars used to incorporate this type of glass in all their windows, but, primarily as a cost-saving measure, automakers switched to using tempered glass in the side and rear windows of vehicles beginning in the 1960s.

*There are other types of safety glass too, though—for example, the mesh-inlayed glass you might find in hospital or school windows qualifies as safety glass.

Where does it come from?

Most often, street diamonds are the remnants of auto burglaries. Auto break-ins are a growing issue: since 2010, the number of car break-ins in San Francisco has nearly tripled.

“On average we replace three windows per week, but we get more calls for price quotes,” San Francisco Auto Repair owner Gary Siegel wrote via e-mail. “Probably three per day.”

Siegel calls San Francisco’s car break-in issue “an epidemic.”

In 2017 alone, there have been more than 12,000 auto-related thefts in San Francisco, according to open data from SFPD’s Crime Incident Reporting system. (Granted, glass wasn’t necessarily broken in every single one of these instances. But typically, if a locked car is broken into, smash-and-grab is the quickest and most logical way for thieves to go.)

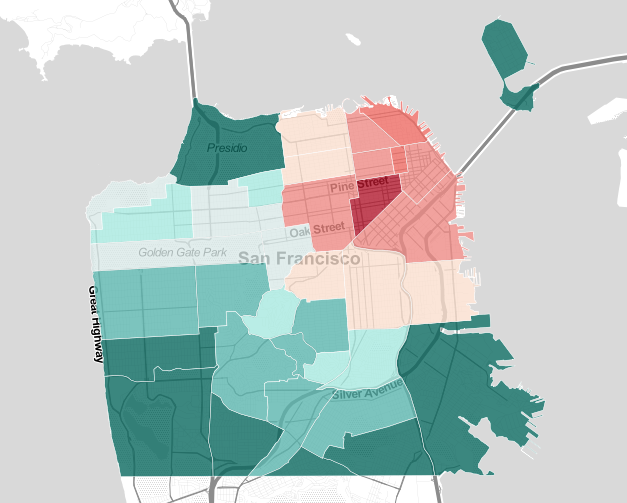

Jieqian Zhang, a graphics editor and data reporter, went so far as to create a live heat map of San Francisco car break-ins in order to help San Francisco residents and visitors figure out how safe it is to park in a given neighborhood. Using this map, if you’re in San Francisco, you can search the area 100 meters (about one block) around your location for specific stats about car break-ins near you.

Where does it go?

According to the San Francisco Public of Department Works, glass on the streets is cleaned up in one of two ways: via hand sweeping or mechanical street sweepers. “We have folks pushing brooms in many commercial corridors,” a DPW representative said. As for the trucks, depending on the area, they come by anywhere from daily to every other week — as you’re likely aware on account of your regularly scheduled car-reparking shuffle.

Street-sweeping vehicles typically work by squirting water onto the roadway to minimize the nasty dust that flies up, while spinning brushes that scrub the street. A cylindrical brush or vacuum then directs dirt, debris and glass onto a conveyor built and into a storage container inside the vehicle. Another kind of truck uses a hydraulic system of air jets to disturb dirt on the road, redirect it toward the truck’s center and then suck it up using a vacuum.

For those whose car has graciously donated glass to city streets, Siegel says that auto-repair shops vacuum it out of the vehicle, and then “it goes in the black bin to the landfill.”

“It’s not recyclable,” Siegel says. Bummer.

What now?

The only thing San Francisco area drivers — or parkers, to be more specific — can do is make their car as undesirable a target as possible. Do not keep anything of value in your car (“The thieves know the hiding spots,” Siegel says), and if you want to go the extra mile, get a club and lock your steering wheel so criminals can’t steal your car too.

And if you see or experience a break-in, don’t just shrug it off and head to the repair shop—report it to the police. That’s the only way the SFPD can know that crime is happening, and the only way they can determine whether they need to increase patrols in a specific area.

Unfortunately, smash-and-grab car burglaries don’t look like a trend that will be disappearing anytime soon. And if it can’t be stopped, we’ll just have to make the best of it. You can report broken glass that needs to be cleaned through San Francisco’s 311 site. And if you ride a bike through the city, slap some Gatorskin tires on your steed (trust me, they’re worth the price).

If all else fails, San Francisco’s street-diamond epidemic sure does lend itself to an excellent arts-and-crafts opportunity. Grab yourself a miniature brush-and-dustpan set, and sweep those bad boys into a storage container to rinse off when you get back home. Street diamonds make for part of a lovely mosaic in your garden or entryway.