My first rave was called Eon. It started in a donut shop on San Pablo Avenue in Berkeley. My friend found out about the donut shop, a.k.a. the Map Point, by calling a phone number listed on the flyer for the rave. I was 16, and it was January 1996.

My acid was kicking in when we stumbled into the donut shop, the fluorescent lights frightening, the rainbow sprinkles fascinating. We handed our five dollars to two guys resembling an ostrich and a bear sitting in a corner with a cash box. They handed over a piece of paper with handwritten directions on it.

I’d entered a disco inside a spaceship inside an enigma. It was way more than a mixtape. It was a movement.

Minutes later, my friend’s boyfriend drove by a dark block of warehouses. We saw a couple of people smoking in front of a door. Trying not to think about my parents paging me to find out that I wasn’t sleeping at my friend’s house, but dropping acid for the first time and excited about going to an illegal underground party, something life changing was about to happen. I could feel it sizzling through my veins along with a deep bass that was thudding through concrete walls.

Walking down a narrow, glowing hallway, I followed my friends into a room where yellow, green, and blue lasers bounced off the walls. The place reeked of cigarettes and sweat. People were fluttering about, quick and slow. The room vibrated electric music that was more alive than anything I’d known possible. The crowd was dancing, smiling, and welcoming us to join. I’d entered a disco inside a spaceship inside an enigma. It was way more than a mixtape. It was a movement.

Fast-forward to 1999. One hundred and four raves later, and even though I was just turning 20, I was already done with the scene. They had turned into massive parties, ones that cost $25, with lines around the corner to get in. I’d survived drug burnout, and after a couple of hours of dancing, my friends and I would say goodbye after complaining about how parties weren’t as fun anymore.

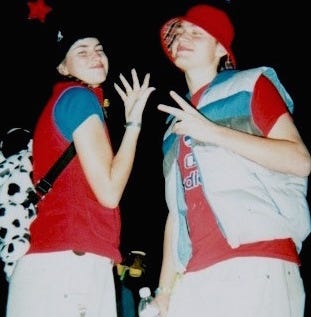

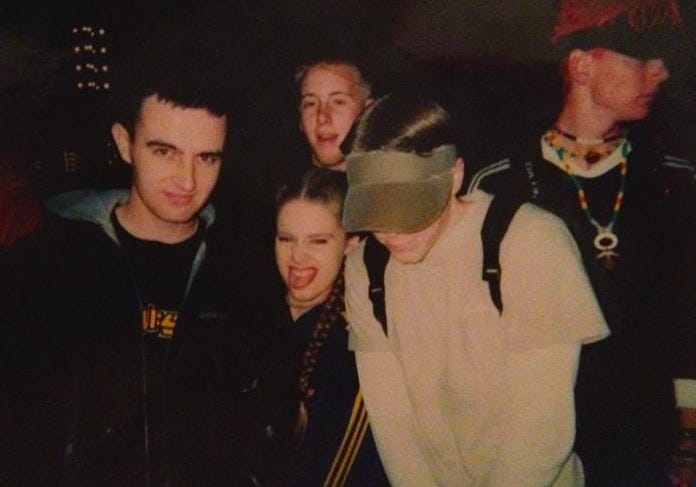

Was that because we were sober-ish or because parties had evolved? Both. I was about to move to New York for college for my next adventure, but I had memories for a lifetime. Memories captured not by phones but by disposable cameras, and nostalgic stories laced with cuddle puddles, glitter, JNCO, Adidas, and lots of hugs (and drugs).

Like my raver friends who complained raves weren’t as fun anymore, San Franciscans started complaining that the city wasn’t as fun anymore. Technology and new money stripped the city of its soul.

The Bay Area rave’s roots resembled a giant acid test at ToonTown’s 1991 New Year’s Eve party in the city’s Design District. That same year, a group of British DJs known as Wicked set up decks on Baker Beach for their free-spirited Full Moon parties. While grunge was pulling the music industry’s focus to Seattle, raving was spreading among locals craving connectedness through music (and drugs).

We lived in a prime area for it. The Bay Area is a magnet for New Age thinking and philosophy. There’s an openness to designer drugs and freethinking left over from the Haight-Ashbury days of acid rock. A groovy nightlife scene was already booming, mainly because of the area’s liberal stance on homosexuality — house music was already playing in mixed gay/straight clubs. And because of the area’s roots in psychedelia, this scene veered toward heavier acid and mushroom use than others.

However, many of the drugs pumping into the rest of the world’s raves were made in West Coast labs, giving California first dibs on some of the cleanest ecstasy of the time. Silicon Valley was a budding technology epicenter. Photoshop was invented in 1989. Early users created rave flyer art—colorful, promotional flyers we’d collect and get lost in while tripping out.

The producers, promoters, and DJs of the original Bay Area rave scene eventually moved on too, some by way of Burning Man (which was already burning), festivals, and EDM. I think we all knew things could never be the same when the movie Groove came out in 2000, though it is a sweet tribute. By 2002, the underground scene was considered dusted when concert behemoths such as Goldenvoice got in on the action, driving out smaller producers. House music was overrun by substyles of electronica, such as drum and bass, trance, jungle, happy hardcore—you name it. In 2003, senator Joe Biden’s proposed RAVE act didn’t pass through legislation, but it exposed the Bay’s producers, slapping them with steep fines or jail time if they continued throwing parties where ecstasy would be.

Fast-forward to 2019. The venue known as the Deli in Mission Bay was where the UCSF Medical Center is. DJ Dan, Jim Hopkins, and Mark Farina are still making music. Feelgood Entertainment’s Vlad Cood (remember his cartoon hat?), who paved the way for permits and Oakland’s Home Base, is celebrating 20 years at his SOMA nightclub, Butter. And about 12,000 ex-ravers who were there share music and stories about the glory days on a dedicated Facebook group.

Like my raver friends who complained that raves weren’t as fun anymore, San Franciscans started complaining that the city wasn’t as fun anymore. Technology and new money stripped the city of its soul, so they naysay. Chefs moved to the East Bay, where rents were cheaper, and longtime locals followed them. Hipsters happened. The music scene suffered, and cultural institutions closed. It seems like the PLUR — the peace, love, unity, and respect — had fizzled. (PLUR is the raver’s credo, coined by DJ Frankie Bones at a Brooklyn warehouse party in the early ’90s.)

Rave was the last youth movement of the century. Throughout the ’90s, ravers were blissfully unaware of the terrorism and technology about to take over the world. We partied hard like it was 1999. Vlad Cood muses, “It was the beginning of the tech revolution, the pulse of the future. We got away with a lot because nobody understood it. The vibe of the beat brought everyone together. When people woke up to that, everyone wanted to be a part of it and make money from it. Everything changed.” The music and spirit of rave was the foundation for the following decades, when dance-music pop and festivals dominated.

Could the Bay Area experience the pioneering spirit of rave again? Well, ecstasy = Molly. Outside Lands and the Treasure Island Music Festival are the annual massive events, while clubs like F8, Monarch, and the Midway spin house and techno. Recreational marijuana is legal — woot — and microdosing CBD and psychedelics are a thing. The underground scene is still unsafe, as evidenced by the Oakland Ghost Ship fire. You can watch live DJ sets online, and some DJs spin vinyl. Candy (as I spelled it back then), or “kandi,” bracelets are in vogue, but don’t get me started on what some raver girls are wearing nowadays, which, unfortunately, isn’t much. Lyft, Narcan, and biodegradable glitter sure would have been handy. And there’s always Burning Man.

You can also venture to Belden Town for the Emissions Festival, where a ’90s raver says, “People are still friendly. They might walk around with a phone in their hand, but we all ran around with disposable cameras in our big-ass back pockets. You’d be surprised by how little things have changed.”

Smartphones — that’s another conversation. Privacy and anonymity contributed to being present back then; we danced as if no one was watching, and no one was. If you’re willing to leave your phone at home and see where the night takes you, you may find some magic, but who’s up for the challenge?

Max Gardner, a techno DJ and producer representing Gen Y, knows what’s up: “Rave culture birthed everything we have now. It also birthed EDM and big club culture. As the cycle shows over time, the older heads get busy with families and careers and have a harder time sustaining, while the next generation grows bigger due to their business mindset. Rave was always a DIY culture. People started their own parties, many of them ignorant of the community before them. It’s contributing to the separation. There are two sides now: the EDM business and the real rave culture.”

Old school, new school—it shouldn’t matter as long as we all try to keep the vibe alive.