The extreme housing crisis in the Bay Area and in many cities across America has left us scrambling to find ways to make the single-family home more affordable in today’s landscape. But rising construction costs and the widening gap between income and home prices should make us ask, Is that type of dwelling really the best fit for everyone today? What about the young and single, the elderly, the impoverished, the freelancer, or the boomerang parent?

Perhaps not. For many, a single-family home is economically infeasible, culturally less desirable, or both. It’s not the silver bullet it once promised to be — perceptions have changed since mid-century, postwar America, and alternative ways of living can and should be provided to accommodate a variety of lifestyles.

Searching for and embracing those alternatives is crucial to confronting our contemporary social and economic issues. One building type in particular, which once served a vital role in San Francisco, could hold some of the answers.

I’m talking about the hotel.

Not long ago, hotel living was very much an American way of life. For many decades, it was an incredibly popular form of domesticity until it was shunned, outlawed, and nearly eradicated.

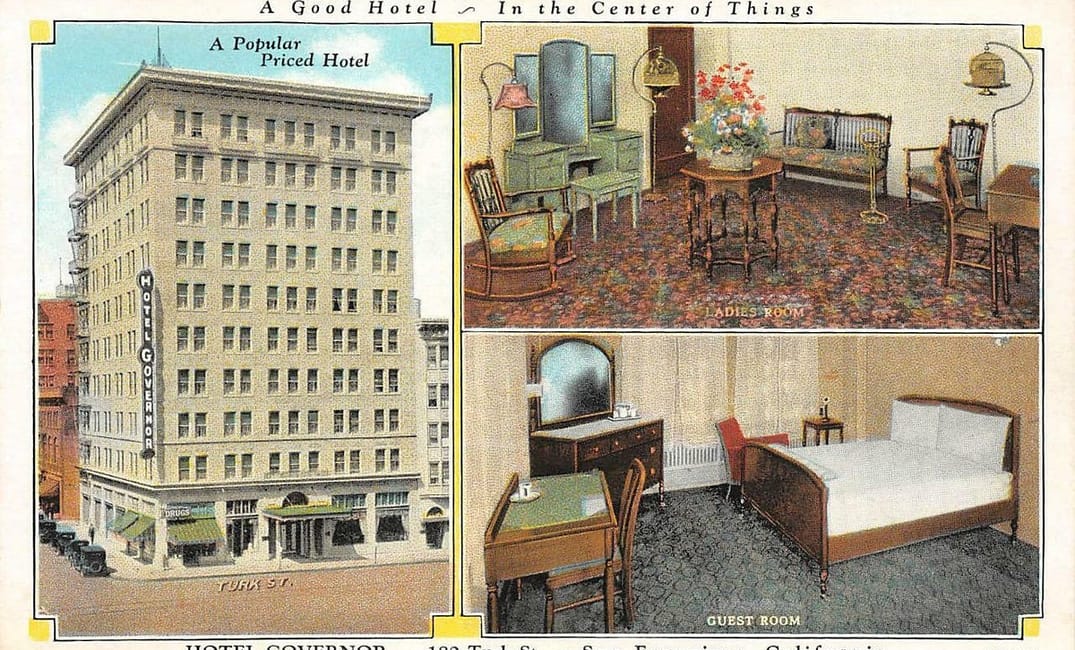

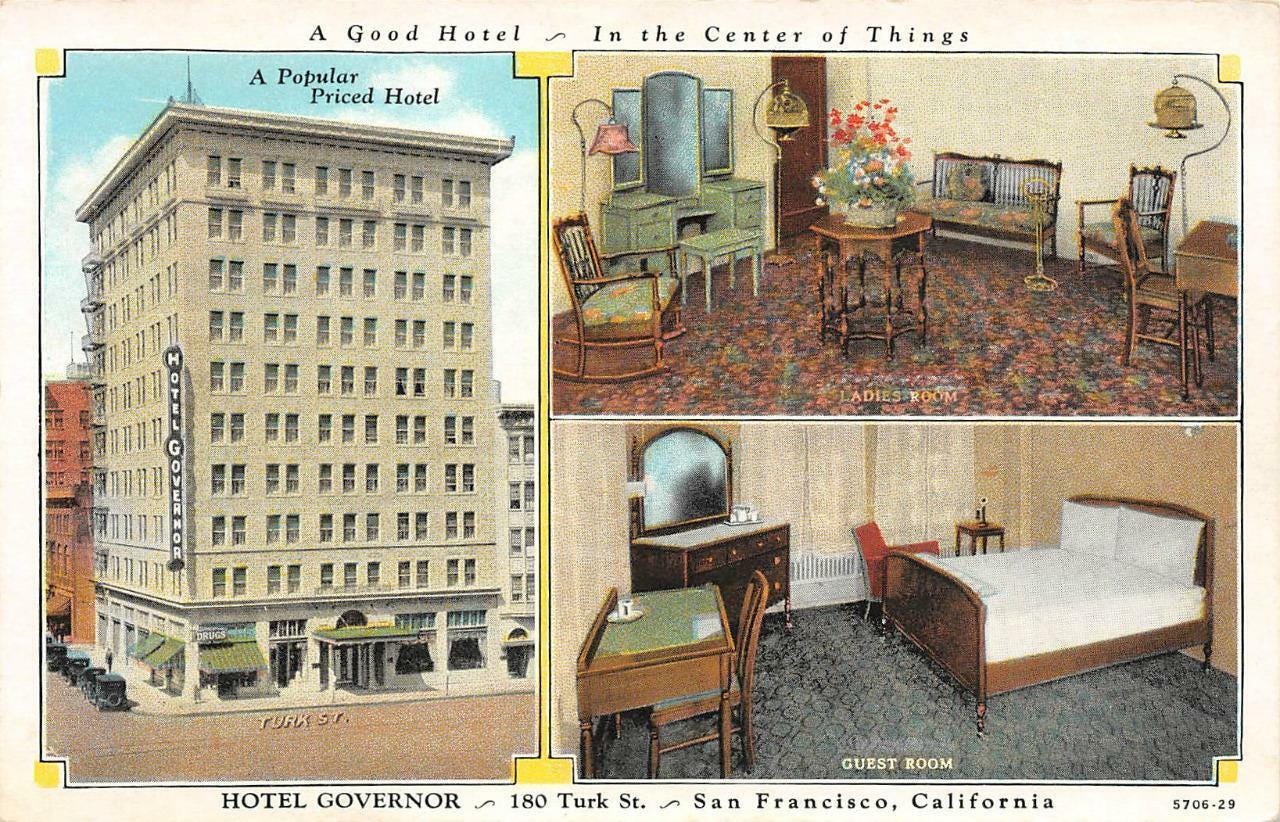

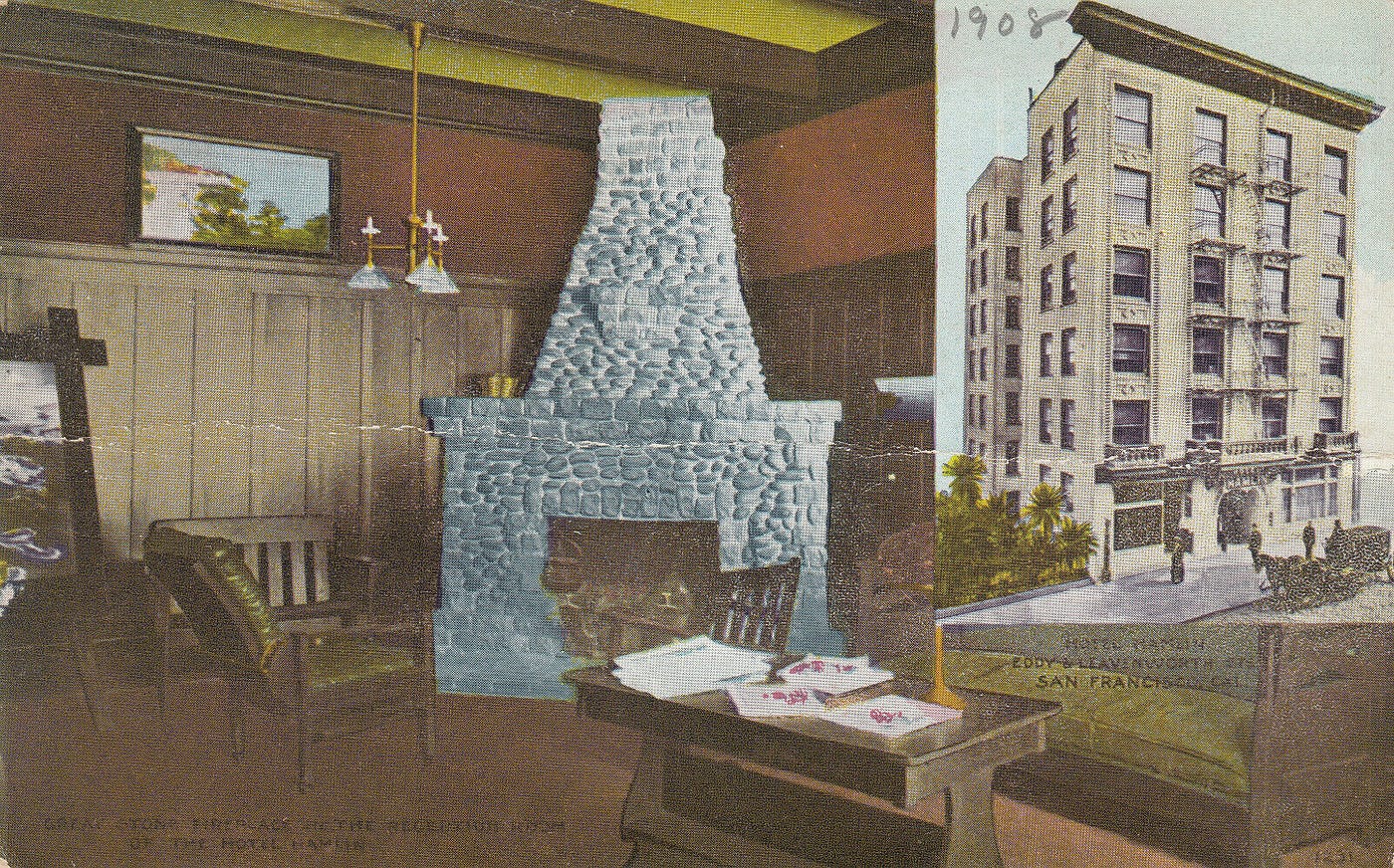

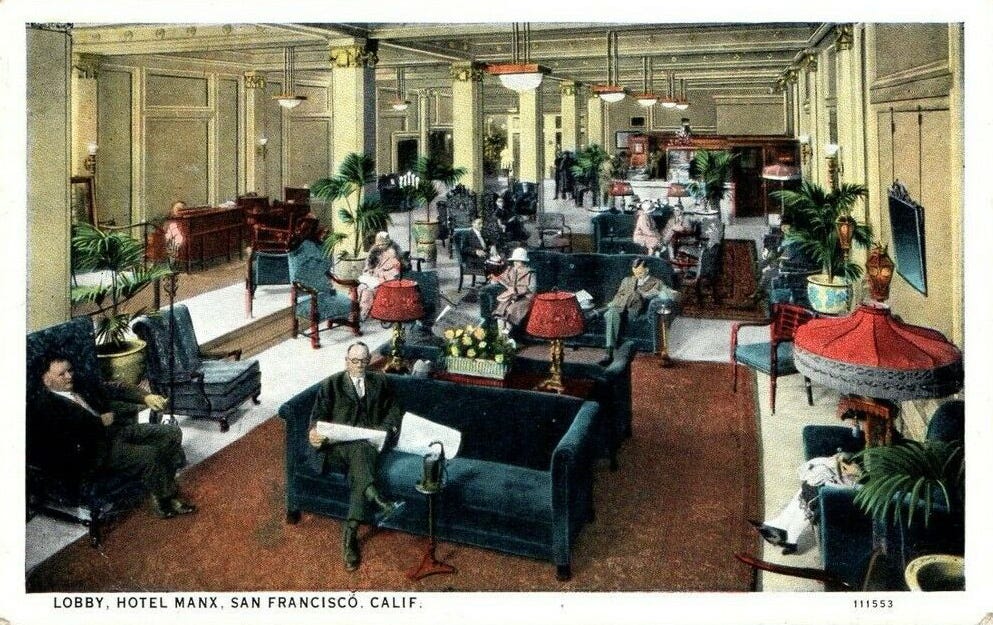

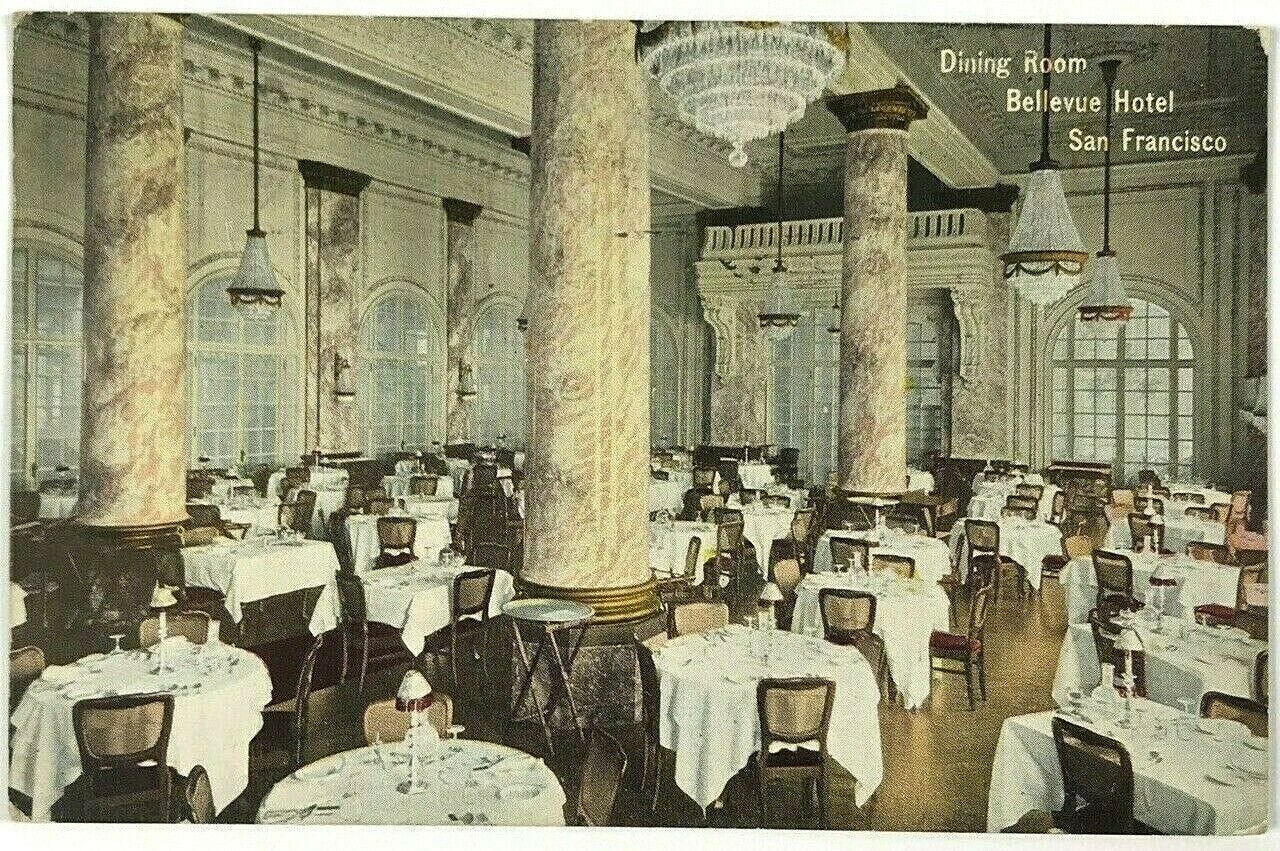

It’s estimated that between one-third and one-half of urban residents in the 19th century tried hotel life at some point in their lives. In 20th century San Francisco, approximately one hotel room existed for every 10 people, and at least half of those rooms were used as permanent residences, meaning they were occupied by the same tenant for a period of at least 30 days.

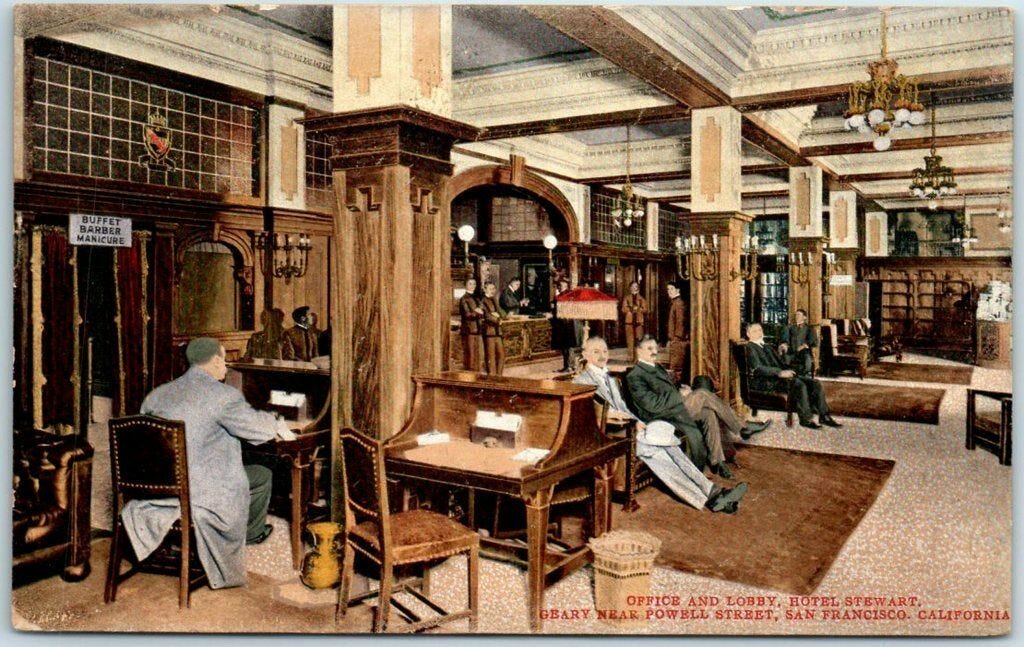

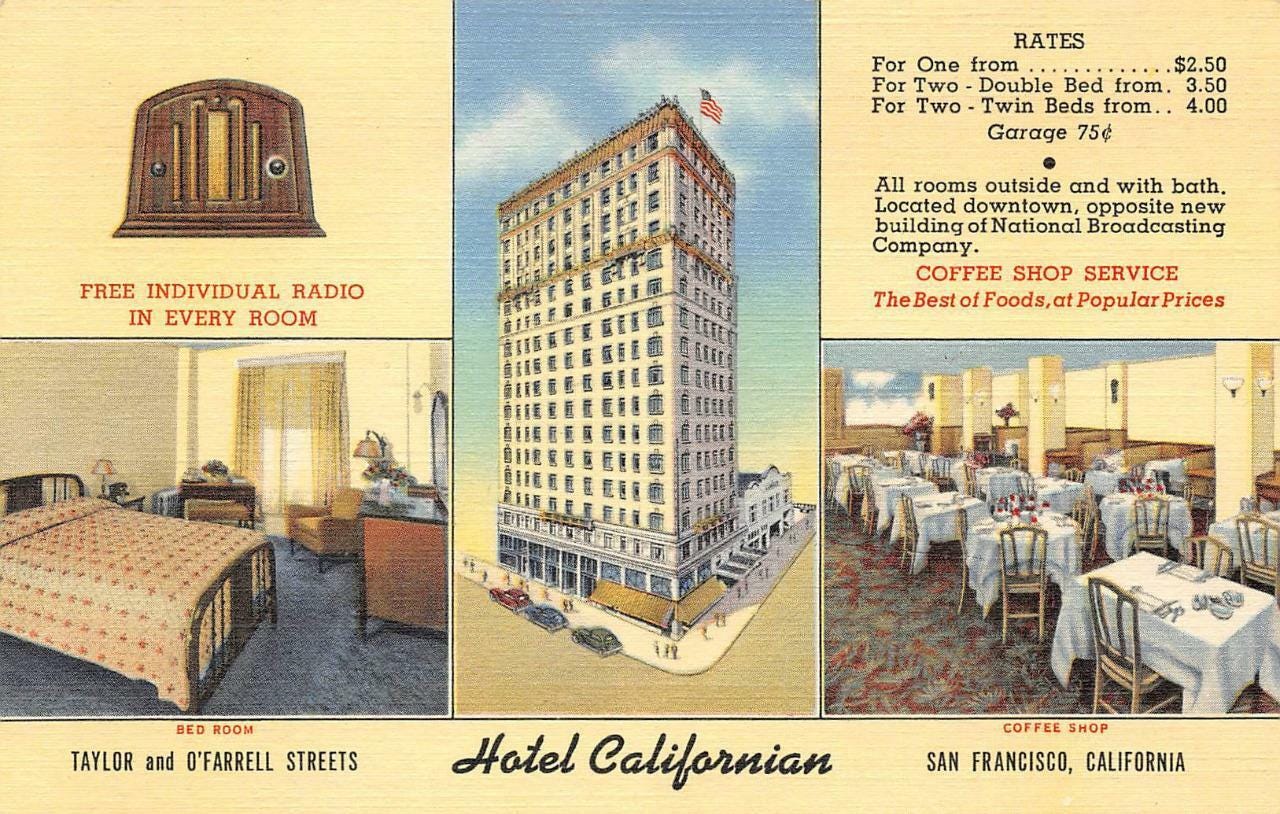

While most hotels today offer only nightly rates, until 1960, the majority of them offered rooms by the month as well. Just imagine the six-room Union Street Inn or the 800-room Hyatt Regency on the Embarcadero, the single-room occupancy (SRO) Cadillac Hotel in the Tenderloin or Nob Hill’s extravagant Fairmont Hotel, as well as the Sheratons, Westins, and everything else in between, all being partially used as permanent residences. That’s what it used to be like in San Francisco and other cities.

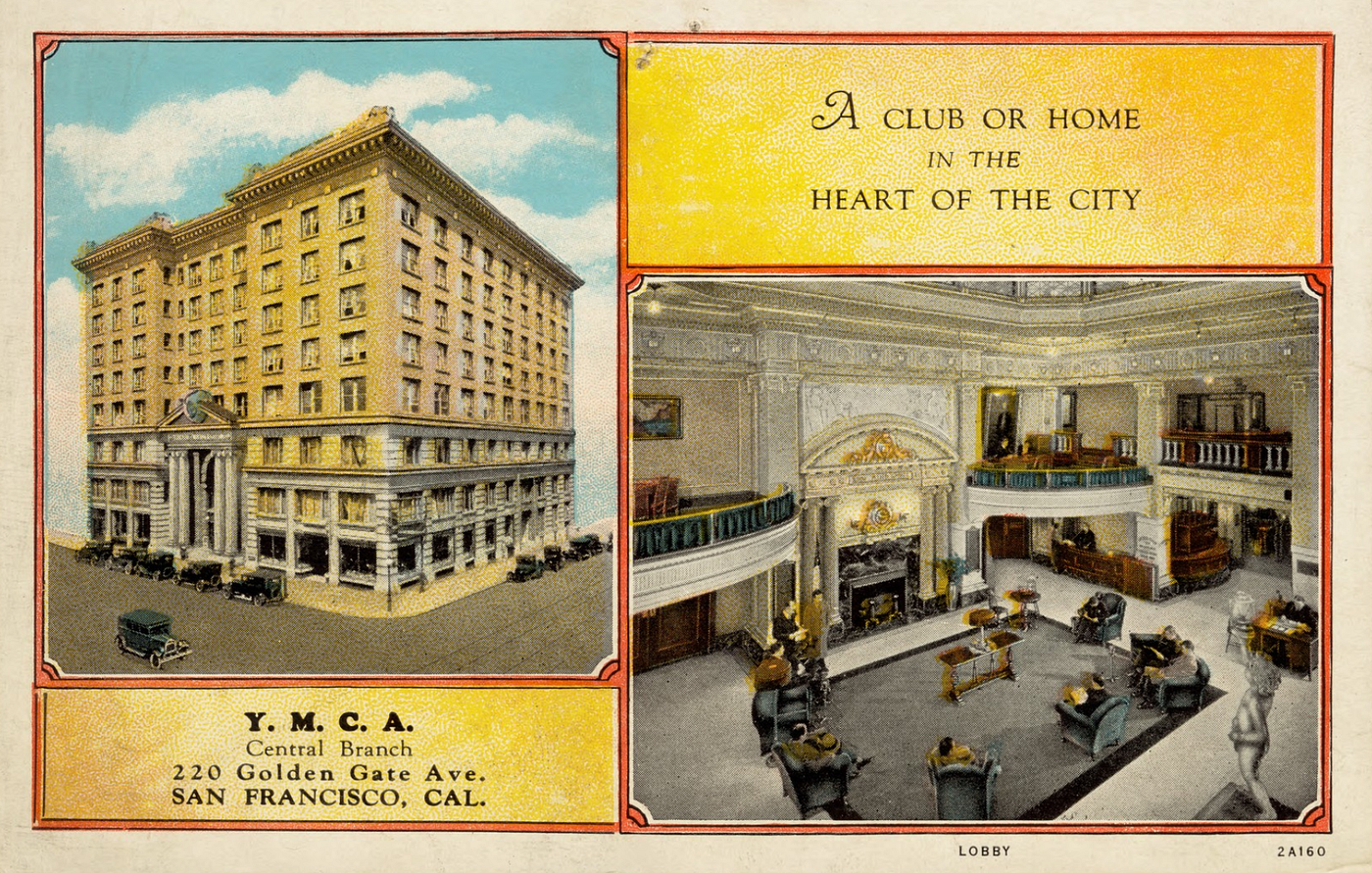

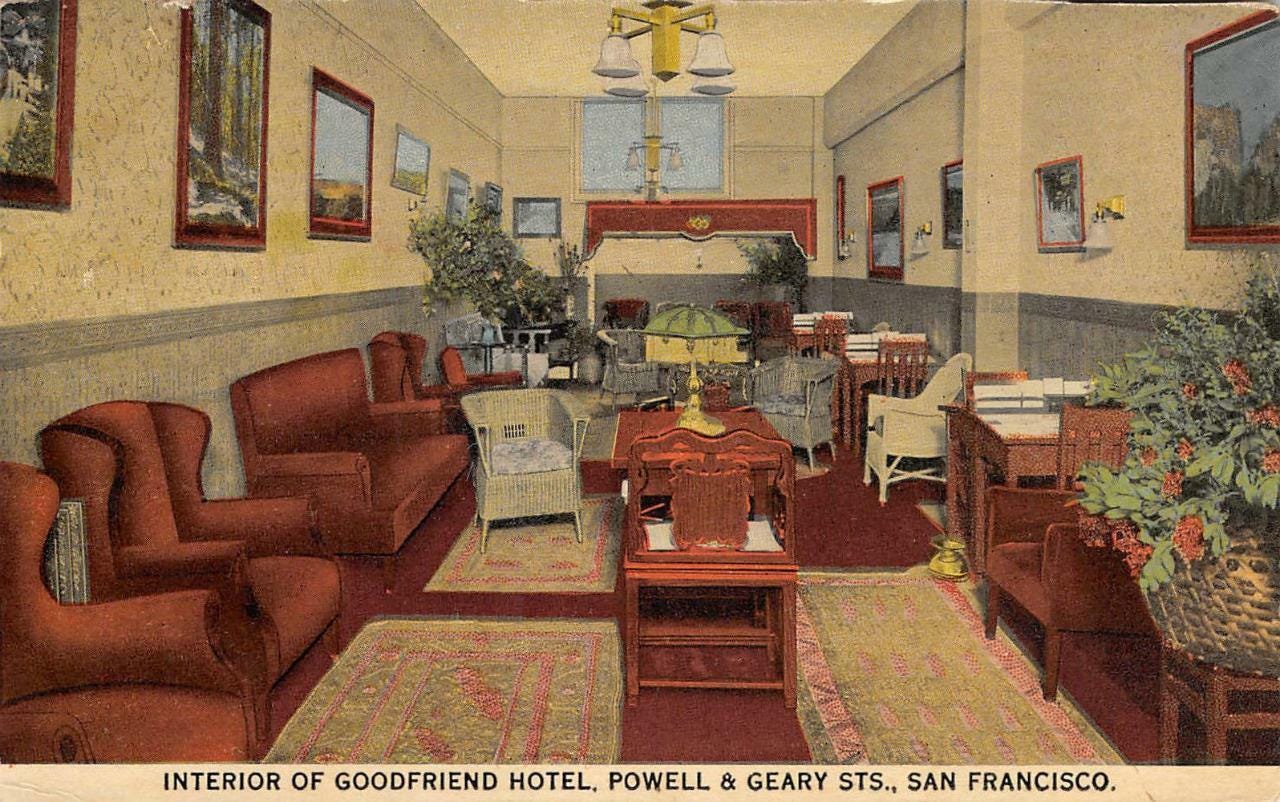

This type of living arrangement was ideal for people in many walks of life. It appealed to nomadic workers, immigrants looking for cultural familiarity, dual-income families desperately seeking alleviation from household chores, and single men and women who were new to the city and seeking the security of a built-in community. But after World War II, corporate and governmental interests incentivized citizens to pursue a form of single-family domesticity, where nuclear families lived independently of each other and owned their own home. Soon after, exclusionary zoning laws were established that alienated and even outlawed hotel living, declaring that hotel residences in the United States were of inadequate size and unsuitable for this new type of family life.

These policies had devastating impacts. During urban-renewal programs of the 1950s, buildings like the Moscone Convention Center in San Francisco removed massive amounts of the city’s housing stock, displacing thousands of hotel residents. Developers were not required to replace the housing supply they eliminated; under the eyes of the law, hotels weren’t considered homes anymore.

By the 1970s, millions of hotel rooms in the United States had been closed down, converted, or demolished. People’s homes were gone, and they were forced into new types of units and living arrangements.

Ever since, hotel life has never really recovered — but not for lack of want or need. Today, we think about hotels as lavish resorts, sterile complexes near airports, or seedy spots for drifters. There appears to be a deep-seated anxiety about hotel domesticity and a social disapproval of those who choose to live this way. The true economic diversity and social vibrancy of residential hotel life is no longer a part of our cultural memory.

In America, hotel living was both commonplace and often preferred. If we are to address the current housing crisis, perhaps it should be once again.

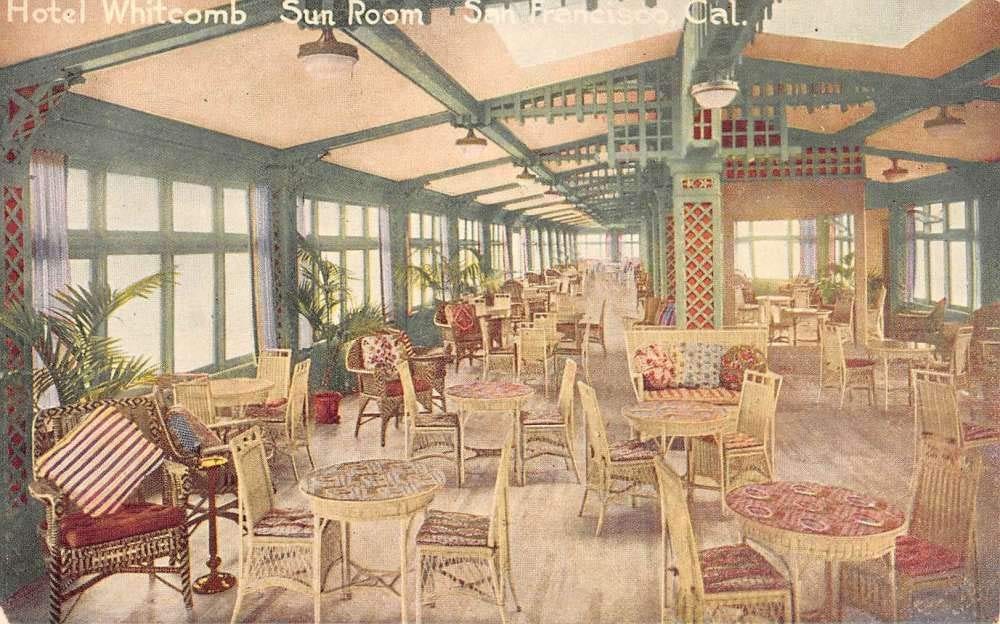

The argument for embracing hotel living is simple and clear: it provides ultimate domestic flexibility in terms of time, cost, size, and sociability.

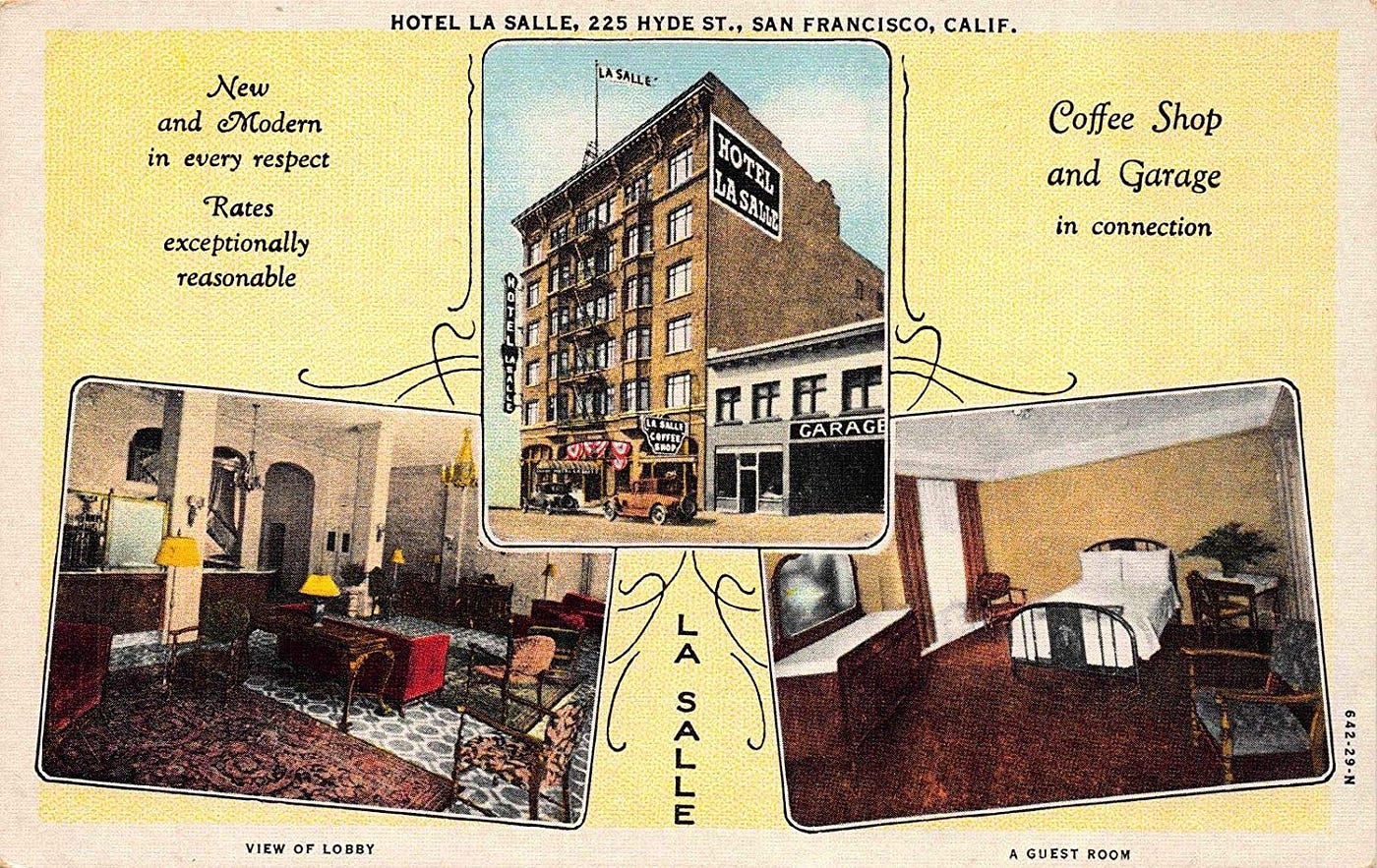

Legally, the definition of “hotel” is vague and varies by district and state, predominantly defined by case law. It’s an umbrella term that goes by many names, such as boarding house, rooming house, motel, inn, flophouse, or SRO.

But at their most basic level, all hotels have three defining traits that differentiate them from other forms of domesticity. First, they offer highly flexible lengths of tenancy — typically by the day, week, or month. Second, they offer amenities, furnishings, and utilities: beds, lamps, desks, soaps, shampoo, water, TV, and power, to name a few. And finally, they provide a range of domestic-labor services, which might include cooking, cleaning, laundering, or childcare. At the very minimum, nearly all hotels offer a room-cleaning service, along with laundered bed sheets and towels.

In these hotels, you might stay for a night or call it home for the rest of your life. You could pay for an empty room or enjoy a fully furnished and serviced life. You could hole up in solitude or comingle in a bustling built-in community. In theory, the hotel could be a drop-down menu of domestic accommodations, a mix-and-match of private or shared amenities and services. The combinations are endless and can accommodate large families or individual tenants, permanent residents or short-term nomads, the extravagantly wealthy or the incredibly poor. Historically, it’s this kind of domestic flexibility that has made the hotel such a popular way of living and could make it popular once again, if embraced.

Despite the benefits, I’m often met with resistance by friends and family when suggesting hotels as both a viable and desirable way of living. The most common complaints:

“Hotel living is too expensive — it’s for rich millennials, celebrities, or the billionaire recluse.”

This is simply not true. Exclusionary zoning and the efforts of large hotel corporations have indeed made many hotels expensive by limiting hotel development to the most expensive locations in the city. Tourist and occupancy taxes also add to the total bill, but despite their seemingly good-natured intentions, these fees often go right back into the hands of the corporations themselves.

This is a policy issue that could change. The bottom line: hotels don’t need to cost as much as they do. Of course, if you’re staying in the Fairmont for a year and getting room service every day, you’re going to pay a premium. However, hotel living does not need to be cost prohibitive; it can often be a more affordable option, and expenses such as water, electricity, cable, gas, and trash are already included in the bill. Furthermore, let’s not forget how expensive homeownership is in its own right — it’s only truly accessible because of generously subsidized government-backed lending practices and policies.

“So are you talking about SROs, then, like the ones common in the Tenderloin?”

The single-room occupancy, or the SRO, is perhaps the most minimal take on the hotel, and has its own unique place in SF. With these units, the resident pays for a lightly furnished room and has access to shared bathing facilities, sometimes with occasional room cleaning. Though typically lacking amenities such as kitchens and private bathrooms, this has meant that SROs have historically been, and still remain, some of the cheapest forms of housing in the city.

San Francisco has a rich history of SROs — such as the Tenderloin’s Cadillac Hotel, North Beach’s Sierra House, or the many profiled in this past article in The Bold Italic — and for many on the economic fringe, the SRO is often the most accessible form of housing. Moreover, unlike houses or apartments, hotels and SROs typically do not require a person to have stellar credit ratings, high incomes, assets, or equity, and they don’t require down payments—all of which can be prohibitive. However, while certainly important and necessary, SROs occupy only a portion of the hotel spectrum.

“What about all my stuff?”

For those who are reluctant to abandon all their personal belongings, I would say that many people don’t want, don’t need, can’t afford, or have yet to accumulate many personal possessions. There’s also a younger generation that’s going full Marie Kondo, preferring access and experience over ownership and accumulation. There’s certainly an appeal to not spending a ton of money on mattresses, tables, dressers, and chairs, and then constantly lugging them with you every time you move.

But even so, hotels can accommodate a wide range of arrangements. Some are completely furnished, while others are delivered vacant.

“Would I have to share things with a stranger?”

Not necessarily. Just like in an apartment or condo, it could depend on what you’re paying. Some hotels, like SROs, have shared bathrooms and kitchens. Mid- and high-end hotels might provide these amenities for each individual unit. But more than half of adults renting in San Francisco already have roommates they aren’t married to or partnered with — in large part because a majority of the city’s housing stock consists of three or more bedrooms — which means that a majority of us are already used to sharing many amenities and services.

Until recently, hotel living has remained an overlooked option for SF and other cities dealing with an affordable-housing crisis. Since the ’60s, it has been socially stigmatized and effectively criminalized as a form of substandard living.

But lately, we have begun to see the seeds of a hotel revival in different forms. Airbnb has proven that there’s a marketplace for all kinds of cohabitation with varying degrees of privacy, tenancy, and shared amenities, although its primary focus is on tourism and short-term stays for tourists, rather than residences. This has the negative impact of removing housing stock in many cities; what’s more, there are arguments that AirBnB has actually contributed to increasing rents and rising housing costs.

Companies such as Common, Starcity, Roam, and WeLive — start-ups that are developing co-living spaces — have also demonstrated the desirability of certain aspects of residential hotel life. However, these companies differ from true hotels in several key ways: they require an application process, have a high social and economic barrier, and thus set up a standard ideal “fit” for who belongs in the communities. Hotels, however, operate in the opposite manner, preferring an anonymous and egalitarian process.

Furthermore, while these start-ups provide certain amenities, such as furniture, utilities, and WiFi, they don’t always offer domestic-labor services, such as cooking, cleaning, and laundering. Perhaps the most radical attribute of the hotel is that it has traditionally considered domestic labor to be similar to that of any workplace job, meaning that it contributes to economic production. If other forms of work deserve wages, the hotel believes that household work should too. Don’t dismiss this too quickly; in fact, it’s really quite sensible. After all, this can lead to service-level job creation, free up those who have traditionally been burdened with hours of unpaid labor at home, or — hear me out — actually pay people for doing work.

Probably the most interesting contemporary example of hotel living is San Francisco’s Red Victorian, located in Haight-Ashbury. Occupied in a hundred-year-old building, the Red Vic, as it is known, is a community-run hotel with a large mix of short- and long-term residents. The long-term residents effectively run the hotel, performing the operational duties and domestic-labor services for credit, which they call community units (CUs). The lobby has undergone many changes over the years; it has been a café, a coworking space, and a vintage clothing and furniture store. Currently, it’s being used for events and community gatherings that range from lectures on democracy and the Bible to talks on tissue engineering for intestinal regeneration. It’s a vibrant and diverse community that has demonstrated the success and appeal of hotel living.

But I also wonder if there’s a way to reintegrate permanent residents into some of our larger, more commercial hotels. Could we introduce policy that incentivizes — or even requires — these larger companies to offer long-term stays at reasonable rates? In view of our recent past, it’s clear that the demand for this kind of hotel living is there. Who knows — it might even make economic sense for these companies, as they look to prevent massive vacancies and large financial losses caused by the Airbnb revolution.

In order to attack the housing crisis in the Bay Area, we need to get creative with our ideas of domesticity. San Francisco’s latest fascination with microunits — apartments under 300 square feet — is one. But there are other more radical alternatives to consider. Not only are they economically viable, but they might even better align with our contemporary wants and needs.

The hotel provides freedom, community, cosmopolitan diversity, and economic flexibility. It offers an affordable, expansive vision of domestic life in ways that apartments and houses do not.

Forget apartments, condos, and single-family homes; we need more people living in hotels. Let’s bring hotel life back into the picture in all its former glory.