If I cue up my favorite mixtape and hit Play when I exit my apartment, the first song is still bopping when I reach the meandering path that winds its way up to the top of Twin Peaks. Half-split wooden posts bolted into the dirt, a staircase rising skyward. I’ve made this climb almost every day since I moved up here last summer.

In the golden-hour haze of sunset and smog, the city drifts out pastel and immaculate, like a 1970s daydream. On crystal-blue weekends, crowds of tourists arrive and solemnly unfurl their selfie sticks on the peak of Eureka. There are a few rotating packs of skaters who daily grind and graffiti the concrete barriers lining the road; they’re as consistent as I am, but we don’t connect beyond a nod. They’re young. I’m an adult. Ships in the night.

I love it when the clouds roll over the mountain — everything outside an arm’s reach evaporates into thick gray, and it feels like being underwater. Silence. Sometimes the fog stays low, and from your clear-skied perch at the top of the world, you can watch it swirling around the city while Sutro Tower floats romantically above.

I haven’t run the numbers on this, but the tower seems to have overtaken the Golden Gate as the city’s signature icon — particularly in the realm of tattoo art. I’ve seen it rising, full-color majestic, among the chaotic flash of a full sleeve, or pinned as rhomboid line art to the underside of a wrist or the back of a calf. You could kill a good 45 minutes looking up photos on the internet , but the thing I’m always interested in is this: how did the artist handle the wires?

From most parts of the city, the tower appears as three freestanding pillars cinched at the waist. Once you get closer, you can see the big groups of cables up top forming a crown of vector pyramids. But when you’re right underneath the thing, you can see that it’s actually crisscrossed and tied down over the entire height of the structure.

And it’s lumpy, asymmetrical and faded. Avocado-green mold is growing near the tree line, and it sprouts rows of mismatched dishes on the crossbeams— bouquets of antennae and curious equipment. It’s more alive up close.

It’s easy to get lost up here.

I’m a nonfiction writer. Well, OK — I guess I’m a failed musician who fell in love with history? At my last steady gig, I held the nonsensical title of “content producer,” which applies equally to someone making instructional videos of the cha-cha, editing digital restorations of priceless Renaissance paintings or translating banned erotic novels from Greek to Angolan.

I can easily lose an entire day at the library patiently scrolling through microfiche or skimming page after page of irrelevant material in thick government volumes in order to find the exact text of some particular ordinance that nobody remembers or cares about anymore. Some of this stuff is online now, but a lot of it isn’t. And anyway, at the library you can ask a question at the reference desks, where the attendants usually know both the answer and what the next question should be. It’s like Google, but better.

One of the interesting things about the city’s history is the continual shifting of what is considered temporary or permanent. Writers like to paint SF as convulsing in the manic ecstasy of a never-ending cyclical gold rush—Wartime Naval Construction, the Summer of Love, Tech Bubble I (Netscape IPO to AOL Time Warner), Tech Bubble II (iPhone to…who knows! Maybe today?). But through it all, our famous hills remained, stalwart and emerald when the stars descended and men wept as their fortunes collapsed. Well…kinda.

The apartment where I live is technically in a development named Vista Francisco. If you take the 37 up to Twin Peaks, keep an eye out just before the second-to-last stop. You’ll pass a sign on the corner that’s tucked under the curling branches of a pine tree. It’s easy to miss—crumbling brownish cinder blocks with a wooden sign in deep maroon, spouting pops of verdigris lichen and run-of-the-mill midcentury sans serif.

The neighborhood up here is purely residential. There are no markets or cafes or venues or whatever. It’s just apartments. But as sleepy and nondescript as it is today, Vista Francisco was actually the subject of a bitter and protracted City Hall battle between its developers and SF’s nascent wave of urban environmentalists in the late ’50s to early ’60s.

After World War II, SF was in the middle of yet another gold rush. Developers were in the process of remolding the city: stretching the downtown skyline ever upward, razing entire blocks via the (bluntly named, socioeconomically questionable and racially fraught) “Slum Clearance Program” and fighting to plant rows of housing on any inch of open space they could find. During the waves of postwar migration and the opening salvos of the baby boom, housing in SF was in high demand and short supply. (Hey, sound familiar?)

The story of Vista Francisco includes shady campaign contributions and backroom deals among the Board of Supervisors; the election of Jack Morrison, a key political firebrand from the environmentalist camp; and the eventual involvement of the NAACP and the Catholic Interracial Council, which spoke out against the exclusionary racial policies of the developer — all with nearly half a million 1960s-era dollars of annual tax revenue on the line.

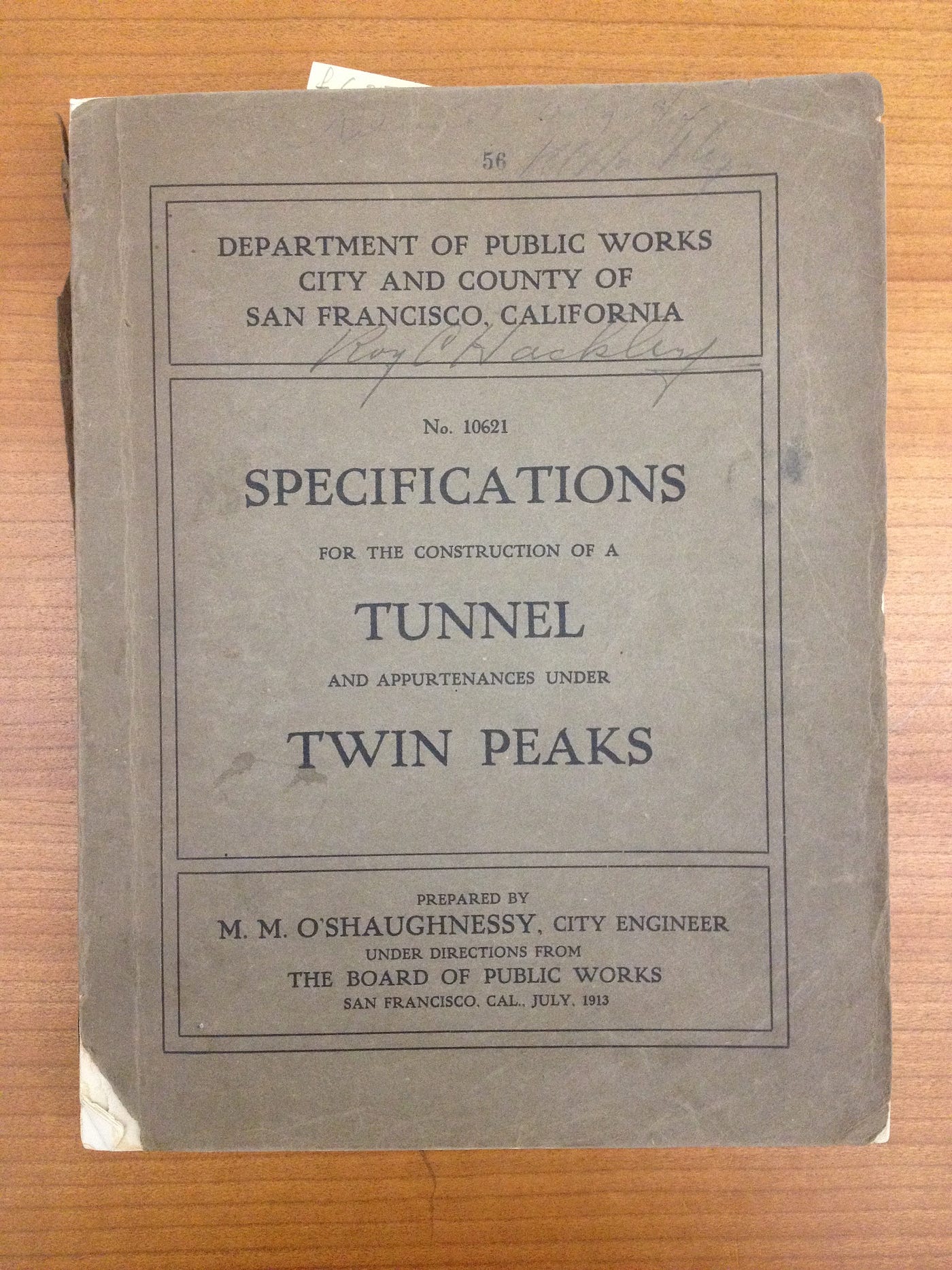

OK, so that’s one thing. But if you wander back even farther, you’ll find all kinds of things. A make-believe Parthenon with a cascading waterfall at the top of the mountain. San Franciscans in their Sunday best, dancing to ragtime in the empty concrete basin of the newly constructed Twin Peaks Reservoir. A provision banning “spirituous liquors” from the construction workers, nestled among the beautiful hand-drafted plates in O’Shaughnessy’s “Specifications for the Construction of a Tunnel and Appurtenances Under Twin Peaks.”

Sutro’s grandson used to live in a shingled castle named “La Avanzada,” complete with conical spires. They tore it down to build the tower, but they kept the two lion statues that flanked the front entrance; they now stand guard at a tiny park in Midtown Terrace. You can visit them and take a selfie.

This is the crazy thing about history: you could spend 100,000 words on a single person or 100 for an entire culture. You have to consider how your perspective fits into historiographical meta-narratives. You could leave out the Ohlone entirely, even though they were up on the mountain longer than anyone else—for millennia, into the hazy reaches before written language — century after century after century after century.

It’s easy to get lost up here.

The rain came in overnight and is supposed to fall all day. From the window of my apartment, the mountains rising to the west and the tower beyond are now invisible, completely enveloped in a concrete wall of clouds.

I twist the segments of my flute together and silently blow warm air through it to bring the metal up to temperature. I bought this dented-but-playable Gemeinhardt from a neighbor on Craigslist for $20. I don’t have any experience with wind instruments — but whatevs, I’ve always wanted to play the flute.

I gaze out the window for a moment — pensively, dramatically — to set the mood and then play an extremely shitty B minor scale. I’ll get there eventually; I just gotta stick with it and mind the embouchure. These days, I feel like I’m looking for something, but I’m not exactly sure what that something is yet. I don’t know whether to tunnel under the mountain or dance on top of it.

It’s easy to get lost up here.

But then again, who knows where you might turn up eventually?