In the 1960s, when the suburbs were taking over America, a keen real estate developer from Pittsburgh, Thomas Frouge, dreamed about building a city on top of the Marin Headlands—Marincello.

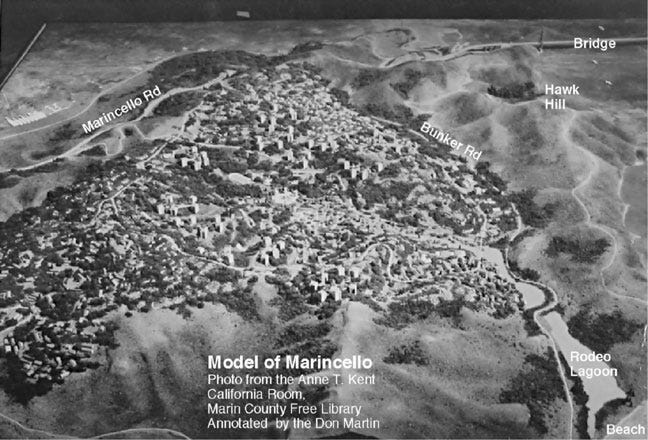

His vision: a city rising from the slopes of the Tennessee Valley, where residents could gaze across the shimmering water, past the Golden Gate Bridge and on to San Francisco. Frouge described the headlands as “the most beautiful location in the United States for a new community.”

But thanks to some persistent conservationalists, red tape and shoddy planning, that vision never came to life—and those rocky headlands just north of the bridge remain a natural haven. The open hilltops and ridges are still cloaked in coastal shrub. The flowing, open natural landscape is one of the most frequented tourist attractions in Northern California.

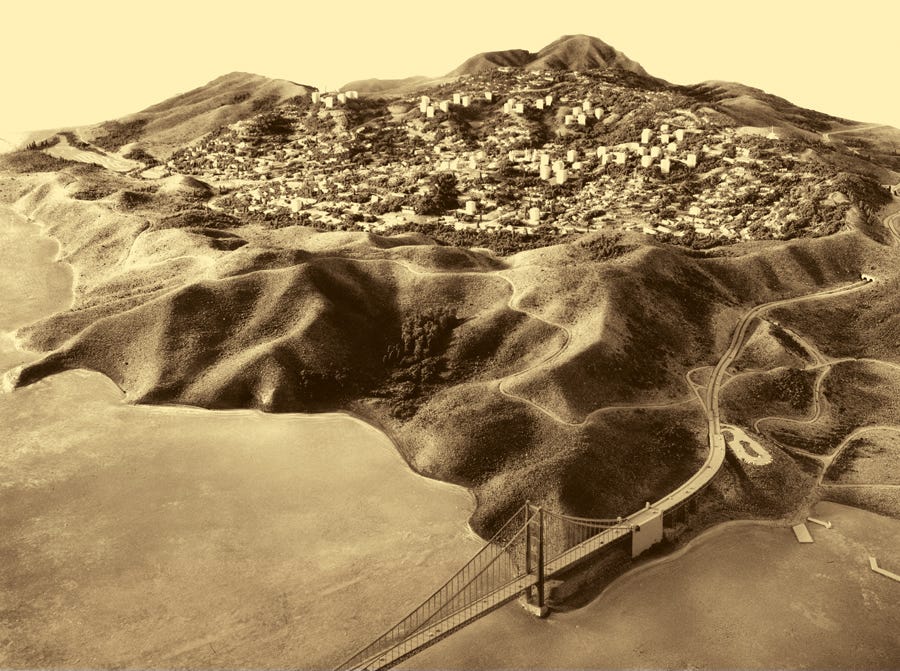

Frouge’s plan was ambitious but pretty simple—30,000 people would live in 50 apartment towers on a 21,000-acre site, alongside single-family homes, low-rise apartments and townhouses. Construction would last 20 years and cost $285 million (what would be about $2.3 billion today). There would be a mile-long central boulevard with leisure pools and trains, and a square bounded by churches called Brotherhood Plaza.

The NIMBYs of the ’60s were not interested in their coastal utopia being covered in concrete.

The developer was always aware of pushback from the local residents and tried to ease resistance by claiming that the open-space architecture would effortlessly blend into the native landscape. However, a closer look into Frouge’s plans revealed that that wasn’t the case—the highest point would have been the soaring Landmark Hotel sticking out of the center of his city. The view from that rooftop bar would have been one of the best in the world.

Glossy three-dimensional drawings were made up in an effort to sell the future homes to potential buyers.

Here’s how that area looks today:

As soon as Frouge and his backers, Gulf Oil, announced their plans, preservationists and residents immediately put forward two petitions protesting the development. The NIMBYs of the ’60s were not interested in their coastal utopia being covered in concrete. Both petitions were ignored by the Marin County Board of Supervisors, who green-lighted the project in November of 1965.

If Frouge had dotted his i’s and crossed his t’s, the view north from San Francisco would look very different today.

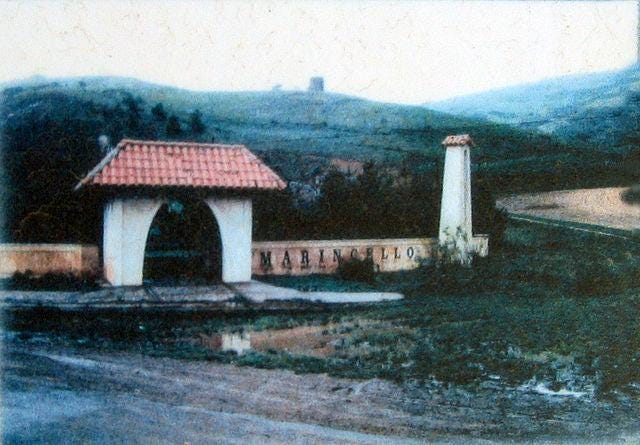

Within a month, workers got started. They built two large gates in Tennessee Valley and carved a street out of the hill to form what would be a boulevard commuters would take in and out of their new idyllic community.

Despite ongoing protests from environmentalists and residents, it seemed like Marincello, the metropolis on the hill, was about to be real.

Over the following few years, the project was repeatedly delayed by bureaucracy and a series of lawsuits brought forward regarding trespassing on privately held land in Frouge’s plans. The gates and central boulevard were standing but still surrounded by the green rocky hills.

Finally, the City of Sausalito brought forward a lawsuit protesting a technicality in Frouge’s planning, which led to the discovery of many more shortcuts he had taken. The entire project was ruled as incorrectly zoned, and Marin County announced that they no longer supported the construction of the city. If Frouge had dotted his i’s and crossed his t’s, the view north from San Francisco would look very different today.

In 1972 the land was sold to the Nature Conservancy for $6.5 million, and the area soon became part of the newly formed Golden Gate National Recreation Area. News footage from the day showed happy environmentalists reacting to the news. “I think it’s very symbolic of a lot that’s happening in the conservation movement,” one unnamed woman said from the windy site of the land purchase.

A crowd celebrated by the Marincello gates.

Seven years after the initial petitions against the development were ignored, California state senator at the time Peter H. Behr told a CBS reporter, “When enough people care enough and work hard enough and for long enough, the right thing will happen,”

The Marincello gates, the only evidence of Frouge’s dream, were removed in 1976.

As we live through a housing crisis in San Francisco, fueled by tens of thousands of people annually heading to one of the most desirable and expensive cities in America, it’s hard to think that 50 apartment towers two miles north of the city could not have alleviated some of the problems. But without that fog shrouding the rugged natural paradise on the other side of the bridge, San Francisco just wouldn’t be the same.

Hey! The Bold Italic recently launched a podcast, This Is Your Life in Silicon Valley. Check out the full season or listen to the episode below featuring Alexia Tsotsis, former co-editor of TechCrunch. More coming soon, so stay tuned!