The morning after we married nearly 50 years ago, Arlene and I took a flight from Cleveland to San Francisco. We had no plans or places to stay on that trip—just a car reservation at the airport and a few weeks for a honeymoon before heading back east.

It was an exciting and divisive time on the West Coast in late ’60s and early ’70s—beautiful but dangerous. The antiwar movement was in full swing; flower power was spreading love dust on a generation of people; and deep political shifts were shaking the nation.

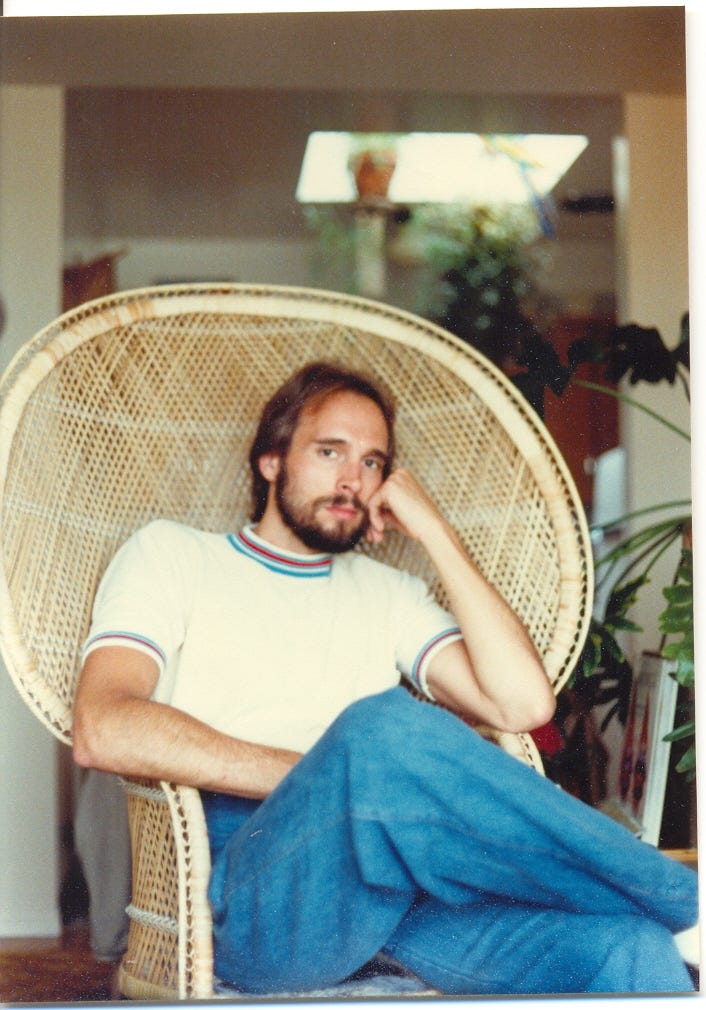

We returned home following that August of 1970 to Youngstown, Ohio, where my younger brother, Phil, was earning his first university degree just before he made the big move to San Francisco.

We loved the City by the Bay, but our visit was temporary. Phil’s move from Ohio in the ’70s was much more major. It was a search for a new way of life.

New Year’s Eve, 1992. I was on the phone with Phil. His voice was distant but clear, despite all the noise in the background at the bar I was at in the Youngstown Maennerchor, an old social club and German singing society in our hometown.

The Maennerchor was where I was wasting life away while Phil fought death in San Francisco. AIDS was taking over a beautiful man, as it did with thousands of others—about 1,600 souls in the 12 months before our talk, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

We were 2,500 miles apart, but I needed to embrace him, so I held the receiver tightly. We were in completely different worlds shortly before midnight. Only time separated us.

We spent our childhood together in a two-bedroom bungalow on a dead-end street filled with families, children, Kick the Can, and softball. We were a family of eight in a steel town in our own wonderland on Maryland Avenue.

Drinks, music, confetti, and dancing surrounded my world at the Maennerchor bar while a vision of his image touched my soul. And this…

“If you’re going to San Francisco

Be sure to wear some flowers in your hair

If you’re going to San Francisco

You’re gonna meet some gentle people there.”

I hear Scott McKenzie’s voice in the song written by John Phillips. It had been a wonderful time in the late ’60s and early ’70s. It was also a tumultuous time characterized by demonstrations and war. If you found yourself in Vietnam, God be with you, friend.

In the ’70s, the City by the Bay opened its Golden Gate to gentle people from all around the world. During our first trip in August of 1970, Arlene and I walked to the intersection at Market and Castro often and frequented shops in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. We were working hippies on our honeymoon, complete with bell-bottom jeans and worn sneakers.

We camped out on Mount Tamalpais with just a bottle of wine and a sleeping bag. We watched the fog softly and silently roll over the bay below us—our carpet of dreams hiding the future.

When Phil moved to San Francisco in the 1970s, he was traveling for a new way of life, one of understanding.

He was a young gay man migrating from cultural conservatism to a community of tolerance and opportunity. He was the third of seven sons, leaving his lonely space in a steel town after earning the first of his college degrees.

We embraced you. All of us, with our hearts and minds. A simple acceptance in a complicated time.

“My brother, it should be me instead of you,” I said into the phone. Tears now. I knew I should be doing better things with my life. I should be the one who was dying, not Phil.

Phil was educated in philosophy and psychology. He studied the intricacies of societies, experiencing the excitement of life as he rode the rapids of the Colorado, bicycled through Europe, and trekked the Himalayas with Sherpa guides.

Though younger, he understood much more about the world than I did. He treated all individuals as special souls. I was self-centered. He was deep and kind.

“No. No you don’t,” he responded in a matter-of-fact tone from his home at Haight and Baker, revealing an acceptance of what was to come.

My brother, my brother. I held you as a child and watched you as a young boy in our neighborhood of friends. We were the Little Rascals of Maryland Avenue. In a blink, you were a young man, leaving for the West Coast when you gently revealed to us you were gay.

And we embraced you.

Mom, of Greek heritage and traditionally Orthodox. Dad, from an Ohio farm and a family of honest, no-nonsense people who lived from the soil. We embraced you. All of us, with our hearts and minds. A simple acceptance in a complicated time.

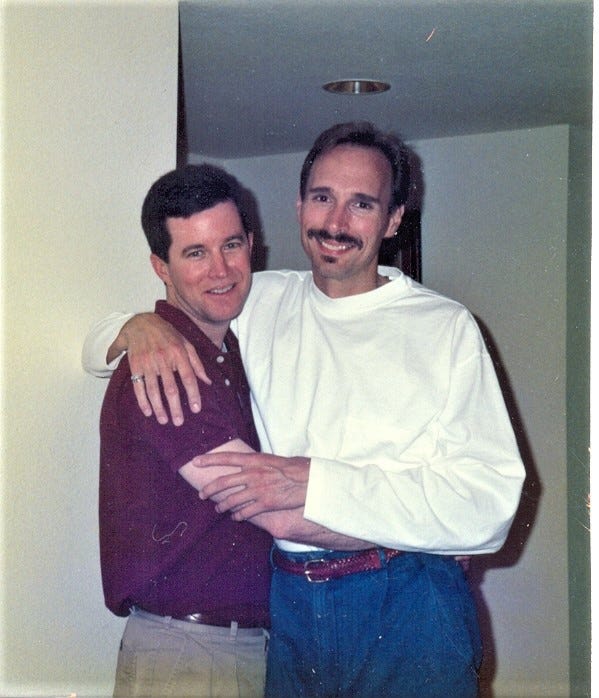

During our trips thereafter to San Francisco, you introduced us to your many friends and your lovers, and to the arts. You took us to a restaurant that employed former prisoners who otherwise wouldn’t have a job. You carried us on your wings of understanding.

Because of you we discovered much more about California than a tourist might ever know. All those gifts you offered helped me become a better person.

You took us to San Francisco’s neighborhoods to learn about the city’s architecture, its diversity, and development in an area not much bigger than Youngstown. You talked about Harvey Milk and your job in city government.

You laughed and called us “touristas.”

At Market and Castro, you pointed to the new electronic crosswalk signs you helped establish that allowed pedestrians to more safely cross that busy intersection. And you shared with us your AIDS-awareness work, the Shanti Project, and your experiences with ACT UP marches in Washington, DC—not to brag, but in a humble way, so as to describe what needed to be done and what was important.

Our trips to Yosemite were fun. You held up a box of cereal for a photo with the Trix rabbit near Mariposa Grove. In the snow. Trix are for kids, all of us kids. And your smile was wide and happy.

Our hike to Upper Yosemite Falls from the valley is forever a memory. “You’re going to need some good hiking boots,” you said with an air of practicality that resembled Dad’s. I did. You protected my feet and opened my mind.

The sun was shining in the valley as we started the climb. Just before the base of Upper Yosemite Falls, the snow started falling. Large, soft white flakes of fresh snow gently covered the narrow path. We sought refuge in a cave and smoked marijuana until the sky cleared. Did I ever thank you? Did I ever say, “I love you”?

You were strong and healthy. You preferred going to the gym in the morning hours before heading off to a full day’s work.

When we embraced that last time in Golden Gate Park, I was overwhelmed with a sense that you were leaving. It was a gentle embrace. You were so frail, so thin—taller than I, but becoming a shadow of life.

On our next visit, your partner, Rick, took us to find your name in the Circle of Friends in the AIDS Memorial Grove just steps from where we had embraced.

HIV/AIDS was all-consuming during our visits to San Francisco in those final three years, beginning in 1990. Ever the teacher, you explained the medicines, such as azidothymidine (AZT), and T cell counts and lesions.

At your memorial service, I spoke a little too loudly. I don’t know why; it’s just that it seemed an effort to push air from my lungs to make my vocal cords work, when words were not necessary.

I rode along with you to meet the kind and busy folks at the clinic. They routinely cleaned the two ports in your chest, one for draining fluid and the other for injections. You asked me to be with you so I could see.

So I would know.

You also introduced me to people who were volunteering and medical professionals working so hard to treat the thousands of AIDS patients, the patients who would die before more advanced medications were developed and administered.

People like you, Philip Jesse Denney.

You enabled me to understand much more than what I had learned by recording your voice in our interview. Brother to brother. As a newspaper reporter, I thought I might ask you a few questions near the end.

I dared to suggest that you might be suffering. “I am not suffering!” you proclaimed, looking into my eyes, into my soul. Ever the teacher, the psychologist.

Our brother, Mike, who lived nearby in Redwood City, called us when you left, peacefully with Mike, Rick, and your friends. You knew it was time.

Knowing how much you loved life, how much you cared for people, and how much you learned around the world, I cannot imagine how you came to peace with the end, but you did.

At your memorial service, I spoke a little too loudly. I don’t know why; it’s just that it seemed an effort to push air from my lungs to make my vocal cords work, when words were not necessary. Not at all.

A quiet calm prevailed among your many friends, family members, mom and dad, and Rick in the glass-lined arboretum in the park, where, just outside in the sun, a single songbird fluttered beyond the green-stained glass.

I wondered if the songbird was really you, dancing at the window to let me know you were excited and that I shouldn’t worry, because you were leaving for another grand adventure of life in the City by the Bay.

And then, without a sound, I knew.