One of my favorite parts of my time coming-of-age in the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1980s and early ’90s was running Bay to Breakers, an annual 12K race across the city showcasing the best of the city’s quirkiness.

A quick note: When someone says they’re from the “San Francisco Bay Area,” like I have, it means two things: they live within a two hour drive of Ghirardelli Square, but they are not actually from San Francisco proper (if they were, they wouldn’t bother with the irrelevant “Bay Area” qualifier).

After all, San Francisco city limits are only 7-by-7 miles and home to just shy of 900,000 residents — smaller than most people realize. This 7-by-7 grid is what gives the Bay to Breakers course its form, crossing the city from end to end, from the bayshore in the Financial District down Market Street, up Hayes Street, through the Haight, into the Panhandle, and winding down through Golden Gate Park to the beach (the “breakers”). Locals have been running this race since 1912. It is typically held in May, but the 2020 race has been rescheduled for September 20.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

The race is a serious, professional competition, and some elite runners come through for both the prestige and a shot at a piece of the total $15,000 prize money split amongst various podiums. When I was a teenager, the great Kenyan Ibrahim Hussein won back-to-back men’s titles.

But, really it’s all about the river of humanity — 100,000 runners connected in a flow snaking across the city, all going one direction, with the exception of the traditional group of runners dressed as salmon, who run the course in reverse.

At the front of the snake are competitive runners who finish before 8:40 after the 8:00 a.m. starting gun. The back of the pack straggles in hours later in the form of a moving party. It’s part Mardi Gras, part Grateful Dead show, part corporate team building. Most people are decked out in some sort of costume or getup, if they are wearing anything at all.

The first year I ran was 1981, when I was 12 and got dragged along by my overactive parents who were then in training for a “we’ve turned 40, let’s run a marathon” crisis.

I remember being too far back in the pack, getting stuck in traffic. During the early miles through the city streets, I shimmied through a six-inch-wide crack between the parking meters and the edge of the curb. I was eager to run and felt disappointed with my time.

The next time, as a scrawny and gangly prepubescent 15-year-old, I was determined to finish the 7.46 miles in under 60 minutes. I made sure to start farther up in the pack, and got pulled along by the energy of the runners around. I don’t remember my finishing time, but I do remember running my ass off.

I have to hand it to my parents for the logistics required to pull off these family outings. This required serious planning, particularly for us coming from the “Bay Area” part of the San Francisco Bay Area — in our case, 30 miles down the peninsula in Palo Alto.

Consider that when you run seven miles in one direction, by definition you have to find a way back to where you started. By the time I was a teen, my dad’s system had been optimized. We would drive before sunrise to the Outer Sunset and street park in any neighborhood walkable enough (say, 15 blocks) from the finish line. Then, ensuring we had the right number of quarters, we’d catch the N Judah, joining the produce-shopping-aunties heading downtown. The whole thing required a 6:00 a.m. alarm clock on an otherwise cozy Sunday morning.

Just after 7:00 a.m. in the Sunset can be chilly, to say the least, given the involvement of Karl (before the fog was even named Karl). My parents would hoard shitty sweatshirts throughout the year, and dole them out on race morning. At the race start, we’d disrobe and dump them at the starting line with the thousands of others who did the same — leaving heaps of garments that would later be gathered up by volunteers for the homeless. True story.

One big logistical problem I remember was how to find each other after the race. It was guaranteed you would get separated from your party at some point. Everyone had the same problem: 100,000 people trying to find each other without cellphones.

There was a solution for that.

At the end of the race, along the beach in the sand (remember this is the “breakers” side of town), race organizers would mount huge letters on poles, one for every letter in the alphabet.

We chose to meet at the letter P. No one had the prescience to consider that each letter would be placed in sequence 50 yards past the next. A… B… C… Good ole P meant an extra half a mile of post-race schlep on the windy, foggy beach in skimpy running garb with the sincere hope of finding your ride home.

By the 1986 running, I was 17 and my priorities had shifted to be farther and farther back in the pack where the fun was. Not as far back as the teams wearing grass skirts and carrying a full tiki bar though. But closer to the nudists.

That year, I somehow ended up in a group who had backpacks full of cans of beer. Running, then drinking beer, then running, then beer, then running. It was fun!

We recoined the event “The Beer to Breakers.”

Over the subsequent college years, I ran it a couple of times since my spring semesters at Duke ended early enough for me to finish finals, hit Myrtle Beach, and make it back to the 415 by mid May.

After college, a critical mass of high school classmates gravitated back and reconvened in Palo Alto. By ’91, we had enough to rally a crew to represent.

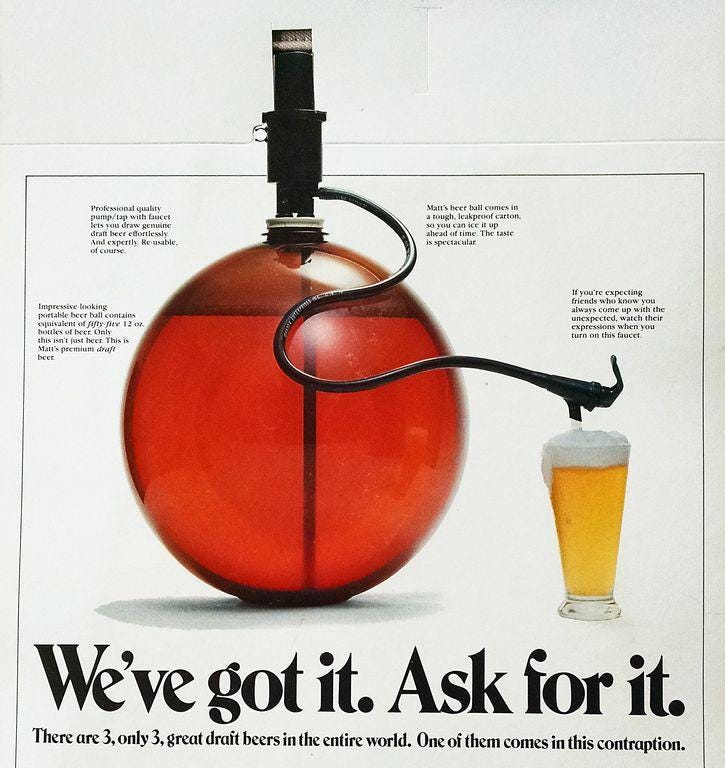

A sturdy looking shopping cart was procured from the Safeway parking lot, which got unceremoniously hucked into the back of a station wagon. A Party Ball™ (look it up, kids), bag of ice, and sleeve of cups was placed in said shopping cart, and we were in business.

Stopping at each mile marker to celebrate with beer just came naturally — gaining momentum and feeling less pain with every mile. Mile three came with the awkward dread around who would push the still nearly full cart up the Hayes Street hill (an 11% incline), which my brother Matt knocked out with aplomb.

Some pro tips:

- It is a bad idea to be one of the runners in front of the shopping cart on the downhill sections.

- It turns out to be important to have a really good set of wheels on your shopping cart when you choose one.

- When you are finished drinking your Party Ball™, and come to the most obvious of conclusions that it’s fun and a good idea to kick your now empty Party Ball™, well, be sure to wear protective footwear.

By 1992, we had the Beer to Breakers dialed in. All you needed:

- One borrowed box-moving “dolly” (with fat soft tires)

- One roll of duct tape

- One pony keg of cheapest beer you can get

- One sleeve of cups

Bonus points for preregistering your keg to ensure it has a race number. Use the tape for the keg’s race tag which won’t fasten with safety pins. No ice or bucket necessary.

The remaining difficulty lay in the execution of rallying a crew of 24-year-olds to actually set alarms and be where they needed to be no later than 6:45 a.m. on a Sunday morning.

Talk was cheap. The odds of flaking rise exponentially the later the pool and pinball would go at the Dutch Goose that Saturday night in the hours before. But with hearty and enthusiastic thirsty runners the likes of Gordon, Matt, Charlie, Sam, Paul, and Scott, we had a strong crew.

By 1992 we had learned to leave the car near the starting line, not the finish line. Not only does this provide more post-race time to sober up, but kegs are a lot easier to move empty than full. Importantly, it also meant a 30 minute later wake up time Sunday morning.

People who live in the peninsula used to exaggerate how quick it was to get to the city, to make it seem like they didn’t live that far from the action. And, indeed, at 7:00 a.m. on a Sunday morning, leaving from the donut shop off Alma and East Meadow, you can get to South of Market pretty quickly.

Once we came off 280, we landed in the sleepy industrial streets where there didn’t used to be a ballpark. It was a ghost town, aside from other runners who nodded at each other knowingly, smugly sharing their savvy in picking the smartest place to park.

We pulled out the dolly and strapped the tape around the keg of Heidelberg. Or it might have been Burgie! (the exclamation point is Burgie!’s, not mine).

In any case, I specifically remember it was $19.95 for 82 lagers — perfect for staying hydrated. We didn’t even need to put down a deposit for the tap, since Paul already owned one.

After securing the barrel to the dolly with many rounds of duct tape, it was time to attach the tap. But I struggled to get the tap on the well-secured keg. The fittings, which should be obvious, were horribly wrong. Paul and I came to a simultaneous and instant unbelievably horrific realization.

It was the wrong tap.

It wouldn’t fit. It wouldn’t work. The fittings were completely different. The cheap keg had some janky hardware used only by the most out-of-date breweries.

We looked at each other in total horror and dismay. We were screwed.

In the middle of industrial warehouses — not a store or resident in the area — at 7:45 a.m. on a Sunday morning, we had a full keg and the wrong tap. Holy shit.

Just as the rest of our crew had gotten organized and started showing interest in the beer situation, but not yet become enlightened to the desperation of the moment, a white van with no markings suddenly pulled up. In my memory, he screeched up to a halt, skidding on a bed of gravel.

A guy inside the van rolled down his window, car still running, and announced: “Hey, you guys got the wrong tap.”

Impossibly, he had sized up our situation and instantly materialized in real time. He pulled over, jumped out of his van and came over to have a closer look. By now, our friends had awakened to the harsh reality of our sobering situation.

The man charged back to his van, slid the side door open, and rummaged in a cardboard box. From the bowels of his van, he yanked out a tap and thrust it into our hands.

“Here. This is what you need.”

We look at this stranger in awe.

We made some feeble attempts at a transaction — “Does anyone have cash?” — but he said not to worry about it and just grabbed the otherwise useless tap, saying he’d trade it out. He chucked our ill-fitting tap into his flimsy cardboard box, slammed the van door shut, jumped behind the wheel, and sped off.

The whole encounter couldn’t have taken more than three minutes.

We all just looked at each other. “What just happened?”

I am not a man of faith. But, simply, this was nothing short of divine intervention. Dude was an angel.

To this day, May 17, 1992, is known by those in the know as the “The Beer to Breakers Miracle.”

Brad Porteus tends to take three times longer than he needs to to make his point, adding tangental side-bar stories as he goes. If his meandering style doesn’t drive you completely mad, there is a lot more where that came from. Check here on Medium or the complete set on porteus.com.