Vallejo, California, a city of 120,000 on the northeastern shore of the Bay and the southern end of the Napa River, has some good news: after years of neglect, people are realizing that Vallejo’s not so bad. The city is blooming right now as it sheds the unfair stereotype of its being a dirty, industrial, suburban wasteland.

Yet the same problems that plagued Vallejo before are coming back to haunt it: namely, big-money interests have put a Bay Area city with a history of economic bad luck in their crosshairs. This time, the antagonist is Orcem America, a formerly European-based company that operates what they refer to as “green” cement-production facilities, which seems like a clear oxymoron. Those scare quotes are not mine — the company’s website actually wedges the word “green” in between scare quotes.

Less funny is the fact that Orcem is proposing to build this cement factory not in an area zoned for industrial use but in a residential area near multiple apartment complexes, single-family homes, an elementary school and a CSU college. The dust this factory would produce, if constructed, would blow directly into much of South Vallejo and Mare Island.

While I loathe the fact that this company picked Vallejo in which to try to build its factory, I understand their logic. The construction of this factory, from a purely capitalist perspective, makes sense for the company. It’s not the first time in the Bay Area that the health of residents and the environment was sacrificed for private profit. Just ask the cities of Richmond, Rodeo, Martinez and Benicia, Vallejo’s comparatively more affluent neighbor. The Bay Area is going through a boom, and during booms, new structures are built; the nearly completed Salesforce Tower is evidence of this, along with a series of other, smaller buildings popping up around the region. Given California’s strict building policies, having a “green” cement factory near all of this makes sense for Orcem.

But it doesn’t make sense for Vallejo or its residents.

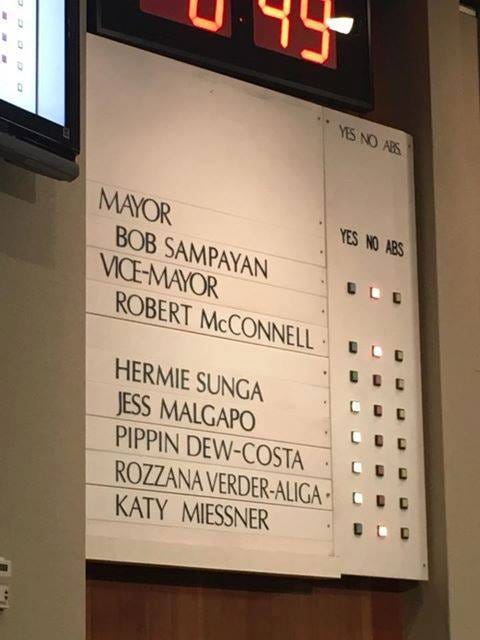

It’s rare to see almost unanimous agreement these days about anything. In this age of information and hyper-partisanship, everyone seems to nitpick about something, but on this one issue, Vallejo seems to unilaterally denounce the Orcem project. If you wander around Vallejo, you’ll notice on many businesses and homes a multitude of signs protesting the construction of the factory. But that hasn’t stopped four city council members, who all live on the eastern edges of Vallejo’s city limits—far from the most detrimental effects of this factory—to try to push the project through.

They’re known locally in Vallejo as the “Orcem Four.”

These four city council members are Pippin Dew-Costa, Hermie Sunga, Jess Malgapo and Rozzana Verder-Aliga. When they voted to extend the process, allowing Orcem more time instead of just killing the project, the crowd at the city-council meeting became audibly annoyed. Indeed, the Orcem Four’s support of the cement factory shows a blatant disregard for their constituents.

This is another example of an historically impoverished city being exploited for financial gain.

But as I learned more about Vallejo’s political structure, the Orcem Four’s actions became less surprising. Many of the politicians in Vallejo who run as Democrats are actually just as pro-business as many Republicans; they merely choose not to run as Republicans because, like in other Bay Area cities, Vallejo’s population leans heavily Democrat. Many of these pro-big-business politicians have formed groups like JumpStart Vallejo to push anti-environment, pro-industry agendas.

Evidence abounds of Vallejo “Democratic” politicians’ conservative views. Former Vallejo mayor Osby Davis made national headlines for homophobic remarks in a New York Times interview. He was also affiliated with a Christian group interested in turning Vallejo into a “city of God,” whatever that means.

The reason why everyone should care about what’s happening in Vallejo isn’t only because of Vallejo, but because it serves as another example of a historically impoverished city being exploited for private financial gain. The democratic process seems to have no effect on Vallejo’s elected officials; all they seem to care about is the money being offered to them by JumpStart and other lobbyist groups.

Even communities outside of Vallejo are worried about the implementation of the Orcem project. One of them happens to be wine-swilling, affluent Napa. And it’s not because Napa has a soft spot for its largely working-class neighbor to the south; it’s because the Orcem factory would not only pollute Vallejo but also have a negative impact on the entirety of the Napa River and the San Francisco Bay. If the water in the Napa River is polluted by heavy industrial waste, it has the potential to cripple their local wine industry and, as a result, severely affect the economy of the entire Napa Valley. Turns out that wine tasting, tourist traps and toxic waste don’t mix. Who knew?

For more information about the Orcem cement factory and the movement against it, check out Fresh Air Vallejo’s website or Facebook page.